|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

|

One-on-One: A Cult of Objectivity: Interview with Massimo Vignelli A conversation at Vignelli's home in Manhattan in 2012 is infused with his sincerity, wisdom, and, of course, his sense of style. By Vladimir Belogolovsky June 2, 2014 Reading many warm tributes to Massimo Vignelli following his death on May 27 reminds me of our many meetings, some of which lasted up to five hours. We hardly talked about work... I am a good listener and he was a great person to listen to.

We first met to discuss the design of my book on the Australian Modernist Harry Seidler (1923-2006), whose dream it was to have his monograph designed by Vignelli. They were good friends for many years and it was natural for Vignelli to agree to work on this project. Our design collaboration lasted a few months and we met a number of times before but, sadly, not after it was done. Harry Seidler LifeWork was released by Rizzoli in April 2014, and it must have been one of the very last projects by Vignelli.

Following our very first meeting, I asked him to be interviewed for my column “Name” in the Russian architectural magazine TATLIN. The conversation that follows took place at Vignelli’s home in Manhattan on February 10, 2012. I will be forever grateful to Massimo for his generosity, sincerity, wisdom, and, of course, his sense of style.

Vladimir Belogolovsky: You were trained as an architect first in Milan and then in Venice, but worked as a glass designer immediately following your graduation...

Massimo Vignelli: I moved to Venice because all great professors from Milan were teaching in Venice then. It was the most progressive school with such professors as Albini, Decarlo, Gordella. When I was in Venice I received an offer from Vennini glass factory in Murano to design glass light fixtures there. So I worked half-day at Vennini and studied half-day at school.

VB: Was it circumstantial that you didn’t immediately start working as an architect?

MV: Well, I did. I worked as a draftsman for a number of architects in Milan and particularly at the office of Castiglioni. I also freelanced and even designed a house which was built and published in Domus magazine while I was still a student. I did many things, like designing catalogs for Venice Biennale, typography design, books, and design for a socialist newspaper. Then I was awarded a scholarship to study in the U.S. and continued to do design work – graphics, products, interiors, silverware – the whole thing rather than doing buildings. You see, doing buildings takes a long time. But I was looking for much quicker ramifications to build my name, so to speak.

VB: It seems that there is a trend in Italy to be educated as an architect and do something else in life. Why is that?

MV: Well, there is a tradition in Italy for architects to be involved in everything – buildings, interiors, stage design, furniture, etc. Once you have a client, you do everything. Culturally we are against specialization. Specialization is an American invention. Also in Italy, we didn’t really go through an industrial revolution. We went from agrarian states right into the modern times. So it was typical for artisans to know how to do everything. That’s why, after the war, Italian architects were involved in everything, including writing about architecture in many kinds of women’s magazines – how to do interiors, how to hang paintings, and so on. Gio Ponti was a key figure then as the founding editor of Domus, which became the first professional architectural magazine. By the 1960s there were many design magazines in Italy. Architects played the leading role in promoting design in the media. It is also important to note that at that time there were no designers. If you were interested in design, you would go to a school of architecture.

VB: You told me that you first went to the USSR in 1954, soon after Stalin died. How was that experience, and what was the purpose of your trip?

MV: That was the time when the first delegations of students and other professionals were organized to go to the USSR. I just wanted to see the country. Aldo Rossi was in my class at Milan Polytechnic, so we were on this trip together. We went to Moscow, Leningrad, Sochi, Tbilisi, and Gori, Stalin’s birthplace... We met local architects who, at that time, still practiced Socialist Realism. I remember having conversations about the fact that the leading architecture in the world in the 1920s was in the Soviet Union. We praised such architects as Melnikov, Leonidov, Ginzburg. I love the work of El Lissitzky – what a fantastic urge for creating new dynamic world! And our Soviet colleagues were telling us that we said all those things because we were fed by a bourgeois view of history. I remember going to the Moscow metro, which is exactly the opposite of what the metro should be, but we were mesmerized and looked like peasants going to Versailles. It was very palatial. Many buildings were being built in that style, which were just like Post-Modernist buildings 15-20 years later. It was totally out of place. It is funny that when first Post-Modernist buildings started to appear in the West I would tell people that I had already seen them way back when in Russia.

VB: You know, it is quite interesting that when I ask progressive western architects visiting Moscow today what building they like most, many of them name the Moscow University building, which is one of the Seven Sisters buildings, the pinnacle of Socialist Realism style in the Soviet Union.

MV: You are kidding me... Well, we came back all very enthusiastic about Russia. We were very impressed by the high level of patriotism there. But as we all know, Modernism prevailed very shortly after and there was no more Socialist Realism practiced there.

VB: What, in your view, is the difference between design and art?

MV: Design is not art because the more there is art the less there is design. Good design helps to solve a problem, but art is not there to solve problems. When design becomes too artistic it really suffers. Design is utilitarian where as art is useful but not utilitarian. One of my main desires is to decrease the amount of vulgarity around by replacing it with things that are more refined.

VB: What about the difference between design and architecture?

MV: They are much closer. Architecture has a component of complexity and permanence. Architecture is a lot more complex than design. But what I try to stay away from in my design is being trendy and fashionable. It should be more about problem solving and targeting at being timeless and not stylized or ephemeral.

VB: It is unusual now to talk about such qualities as timeless. Instead, architecture often strives for being open-ended, adaptable, and therefore not fixed and not defined for eternity.

MV: I never hear these things from such masters as Peter Zumthor, Tadao Ando, and David Chipperfield, or system architects Norman Foster and Renzo Piano. Steven Holl is another great example of a sensitive architect, and SANAA – their work is always based on serious investigation and research. All of these architects have great intelligence and their buildings share such great architectural quality as permanence. I hope their buildings will last for hundreds of years. It is of course different for such “haute-couture” as Zaha Hadid.

VB: You don’t seem to like her work. Have you been to any of her buildings? They are quite something!

MV: The one I kind of like is her Contemporary Art Center in Cincinnati, but that is because it is the least Zaha Hadid-looking building. I don’t like her work because it is a part of fashion system which is based on obsolescence. I think to design buildings that become absolute and passé in just a few years is a social crime. I think good architecture should last forever. Good design should last forever. I don’t think that the dining chairs that were designed by Mies in the 1930s look passé. They still look and feel great. You can’t design anything just to try to reach a particular appearance – it is pure stylizing. It is only important from the point of view that it represents a particular period.

VB: What about Frank Gehry?

MV: He is great! He is different because he has a very rigorous process. He defines order and hierarchy, and functions as a good Modernist. And then he starts to play with the form or the surface to energize the project, but only after the overall scheme is solved.

VB: How do you balance between solving a problem and making a statement?

MV: Well, if you solved a problem you made a statement!

VB: Any examples from your own work?

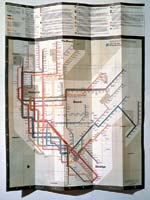

MV: Plenty. For example, the New York City subway map. It shows how to get from point A to point B without any kind of distraction.

VB: And what is the statement?

MV: Clarity. All previous versions were cluttered with unnecessary information. My job was to clean it up. I also enjoy working on system design and developing corporate identities. I am not looking for developing a personal style in design. I don’t have a cult of personality, but I do have a cult of objectivity. Subjectivity is very irritating. Hadid is the goddess of subjectivity. On the other hand, I love the work of Jonathan Ive, the designer behind Apple products who has done a fabulous job by looking for objectivity and staying away from subjectivity. I think Ive is the best designer in the world today.

VB: Would you say that Hadid is more subjective than Gehry? Or is it really a matter of personal preference?

MV: I think it is a matter of the end result. Frank is a terrific artist. He has invented a kind of architecture that is entirely his own. It works, and it is sensational. There is no arrogance in his work.

VB: What are some of your own favorite projects?

MV: I like the work we did for American Airlines. It wasn’t just a logo, but a whole system – ticket design, stationary graphics, timetables, American Airlines magazine, Admirals Club design. I love designing books. There must be thousands that we have designed over the last 60 years. And if you put my fist book and last next to each other you will recognize one hand.

VB: Were you ever a part of any movements? For example, some designers followed Alchemia and the Memphis Group from the 1980s.

MV: None of those. Because what they tried to do was to bridge the gap between design and art. They did what media wanted them to do – something shocking. And once it is in the magazines you start believing in its own significance. But these movements that were all very trendy at the time are now long gone. Ettore Sottsass was the founder of the Memphis Group. He was a terrific designer and a good artist, but you can’t combine the two. Those furniture pieces he did at the time are not design and they are not art. They are not utilitarian and they are not useful. In my own work, I never pretend to be an artist. I try to stay as far away from that notion as possible.

VB: When I asked Gaetano Pesce what he thinks good design is, he said that good design is a commentary on everyday life, a commentary on the real world. What do you think?

MV: It is an artist’s approach. I think there are so many other ways to make a comment or a statement. You can write, play, perform... I don’t think a chair should be a comment. A chair should not be a capricious sculpture. It should be about how comfortable it is to sit in. That’s all.

Vladimir Belogolovsky, founder of the New York City-based Intercontinental Curatorial Project, curates architectural exhibitions worldwide. Trained as an architect at Cooper Union, he is the author of the books Felix Novikov; Green House; Soviet Modernism: 1955-1985; and Harry Seidler LifeWork. His “Harry Seidler: Architecture, Art and Collaborative Design” exhibition is traveling Europe, North America, South America, and Australia from 2012 to 2015. vbelogolovsky@gmail.com

More by Vladimir Belogolovsky

One-on-One:

Architecture is not exactly global: Interview with Orlando Garcia

One-on-One:

Revolution in Architecture: Interview with Gregg Pasquarelli, SHoP Architects

"Harry Seidler: Architecture, Art and Collaborative Design" A new traveling exhibition celebrates the 90th anniversary of the birth of Harry Seidler, the leading Australian architect of the 20th century who followed his convictions and vision.

Colombia: Transformed / Architecture = Politics The curators of the exhibition making its world debut in Chicago this week throw the spotlight on five Colombian architects who leverage brick, concrete, and glass forms to improve the lives of ordinary people.

One-on-One: We architects are politicians: Interview with Giancarlo Mazzanti "Now is the time to think of how architecture can change the world. We architects can assume that role and make a real difference in how people live and behave."

One-on-One: Architecture that leads to a point: Interview with Daniel Libeskind "Every building, every city should have a story."

One-on-One: Architecture of Emotion and Place: Interview with Bartholomew Voorsanger, FAIA, MAIBC The architect's aspiration to create expressive, dynamic spaces is absolutely the key to his work.

One-on-One: Architecture as a Social Instrument: Interview with Bjarke Ingels of BIG It is not for nothing that this young architect is referred to as the "Yes Man" with a willingness - and ability - to please just about everyone.

One-on-One: Putting Colors Together: An Interview with Will Alsop For Alsop, it is the act of painting, the state of losing control - its imprecision and intuitiveness - that best define his initial vague intentions - and what ultimately brings him close to the mystery of inventing new architecture.

One-on-One: The Art of Ennobling Communities: Interview with Sara Caples and Everardo Jefferson These architects have proven time and time again that architecture can transform reality and change attitudes.

One on One: Elusive Architecture: Interview with Kengo Kuma "I want to create a condition that is as vague and ambiguous as drifting particles. The closest thing to such a condition is a rainbow."

|

(click on pictures to enlarge)  ©Vignelli Associates Vignelli Red Book  ©Vignelli Associates 2006 Heller Lounge Chair: “A chair should be about how comfortable it is to sit in. That’s all.”  ©Vignelli Associates 1979 Ciga Glasses  ©Vignelli Associates 1977 St. Peters Church, Manhattan  ©Vignelli Associates 1976 Bicentennial Poster  ©Vignelli Associates 1972 Heller Stackables  ©Vignelli Associates 1972 Bloomingdales Bags  ©Vignelli Associates 1967 American Airlines Corporate Identity  ©Vignelli Associates 1966 NYC MTA Subway Map  ©Vignelli Associates 1966 Knoll International Poster |

© 2014 ArchNewsNow.com