|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

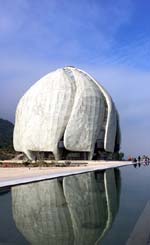

Chrysalis of Crystal The award-winning Bahá'í Temple of South America, designed by Hariri Pontarini Architects, proffers a new kind of sacred space. By Michael J. Crosbie December 21, 2017 On a misty morning, the Bahá’í Temple of South America, nestled into the foothills of the Andes Mountains overlooking the sprawling city of Santiago, Chile, can appear as a mysterious, other-worldly object, perhaps a visitor from another planet.

When I visited the temple, designed by Toronto-based firm Hariri Pontarini Architects, I was not prepared for the power of this transcendent space. One moves toward the temple first from below it, treading along a series of nine pathways and gardens that radiate through the landscape. The paths are not direct, so one experiences the temple from different perspectives, noting how light strikes its variegated exterior surface, which almost looks like a chrysalis. As one comes closer, the 10,000 exterior cast-glass panels, each a different size and shape, glint with reflections on their surfaces, and are replicated back into the earth by nearby pools of still water. When you arrive next to the temple and look up, the cast-glass panels have a visual depth in which one can perceive a varying mixture of clear-to-opaque glass, alive with light.

Stepping through one of the nine portals, the temple mushrooms over your head. It is impossible not to throw your head back and gaze at the swirling vortex of glowing marble that spirals high above you. Slivers of clear glass separate each of the nine veils of light, and cascade sunlight along their gently warped surfaces. The entire dome ensemble appears to pinwheel in a counter-clockwise motion. At the very center is a small, circular oculus that displays the Arabic words “The Greatest Name.” The temple interior’s forms and surfaces literally move as they stand still. It’s as if you are spiritually elevated into the welcoming folds of the dome, lifted into the heaven of its space.

The first temple for the Bahá’í faith in South America reflects the openness of this religious community. The design parameters were fairly straightforward: the temple needed to have nine sides with nine portals, symbolizing its access to anyone of any faith (or no faith). Early on in the design process, architect Siamak Hariri (who explains the history of the project in a TED Talk) gravitated to a circular building with no front and no back, which could be approached from any direction. Hariri describes the temple’s geometry as reflecting the Bahá’í faith’s emphasis on “completeness and perfection,” allowing anyone to express their beliefs (this religion has no clergy).

In reading Bahá’í religious texts, Hariri found a passage that speaks of the power of prayer: “A servant is drawn unto Me in prayer until I answer him&hellipIf his prayer is answered, his very being becomes embodied light.” The architect wanted to literally make the temple glow with “embodied light.” The temple enclosure is conceived as two layers of glass and marble, separated by a layer of steel structure. The exterior layer is borosilicate cast glass, which has a milky appearance that captures ambient light and appears to literally glow. The interior surfaces of the nine-sided dome are covered with translucent white marble from Portugal. Nine metal-clad doors encircling the worship space pivot open to admit worshippers into the temple, which can accommodate 600. The structure was designed to mitigate the effects of earthquakes (common in this part of the world).

Hariri says that he set out to create a “new kind of sacred space” – a very ambitious goal, given the thousands of years that human beings have been creating houses of worship. In the year since its completion, the Bahá’í Temple of South America has become a work of architecture for the ages.

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) and the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) recently recognized this unique work of architecture for its innovative design and path-breaking use of materials. The AIA bestowed its 2017 Innovation Award for Stellar Design, describing the temple as “South American poetry at its best.” The 2017 Innovation in Architecture Award by RAIC described the temple as “&hellipa project of such extraordinary ambition&hellip” Hariri Pontarini’s design was selected in an international design competition that drew 180 submissions from 80 countries.

Michael J. Crosbie, Ph.D., FAIA, is an architect who teaches architecture at the University of Hartford and is the editor of Faith & Form magazine.

Also by Crosbie:

Sitting Down with Kevin Roche: "I learned everything I know about architecture from Eero." "The most important thing one can achieve in any building is to get people to communicate with each other. That's really essential to our lives. We are not just individuals, we are part of a community."

Why the Starchitect Debate isn't "Stupid" Starchitecture is just a symptom of a much bigger problem in the profession.

Crowdsourcing Design: The End of Architecture, or a New Beginning? Why the criticism that crowdsourcing design sites like Arcbazar are taking jobs away from architects doesn't wash.

It is always Friday afternoon in Dealey Plaza An urban setting seared into the national consciousness.

In "New York Dozen: Gen X Architects" by architect Michael J. Crosbie, the framing of each architectural firm is extraordinary.

|

(click on pictures to enlarge)  Michael J. Crosbie Bahá’í Temple of South America: At the center of the dome is a small oculus that displays the Arabic words “The Greatest Name.”  Michael J. Crosbie On a misty morning in the foothills of Chile's Andes Mountains, the new Bahá’í Templee is shrouded in blueish light.  Michael J. Crosbie Temple reflection in a still pool.  Michael J. Crosbie The temple has nine portals and a cast-glass exterior.  Michael J. Crosbie Detail of canopy and cast-glass wall over a portal.  Michael J. Crosbie Thousands of cast-glass panels create a variegated surface.  Michael J. Crosbie Detail of exterior cast glass has a glowing appearance.  Michael J. Crosbie Combinations of natural materials are used throughout the temple interior.  Michael J. Crosbie The interior of the temple's dome is sheathed in thousands of pieces of white marble.  Michael J. Crosbie Sunlight from clear glass windows cascades down the dome.  Michael J. Crosbie Arcs of clear glass allow direct sunlight into the temple's worship space.  Michael J. Crosbie Play of light on the pleated surfaces of dome's interior. |

© 2017 ArchNewsNow.com