|

|

|

|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

|

|

Urban Aria: Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts by Diamond and Schmitt Architects

Toronto: The art and science of architecture fuse to create poetry of form. by Effie Bouras, Assoc. AIA October 21, 2003 Convinced that clarity of opinion is derived from no prior contact with a subject (or, in this case, object), I purposefully avoided all opera house-speak regarding the unveiling of the design for the $150 million Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts, the new home of the Canadian Opera Company (COC). That is, of course, until September 15, when Jack Diamond, FRAIC, Hon. FAIA, co-principal of Diamond and Schmitt Architects, presented his vision to a full house in the Dominion Ballroom at the Sheraton Hotel in Toronto. Diamond did more than simply describe his latest contribution to the architectural scene in Toronto, but in the true tradition of drama – and in keeping with the theme of the evening – he set the stage. Standing in front of a picture window that framed the compelling backdrop of the busy Opera House construction site, Diamond mused, “We have captured the characteristics and qualities of the greatest opera houses in the world,” as he gestured to the site as if the building had already come alive with a thousand voices. The Four Seasons

Centre for the Performing Arts will be situated on the southeast corner of one

of Toronto’s busiest intersections – Queen Street and University Avenue. Designed

mainly for the needs of the Canadian Opera Company, the 2,000-seat theater will

also be home to the National Ballet of Canada. An

architecturally transparent “City Room” that faces University Avenue will serve

as the chief frontage for the building, creating a very visible connection with

the city through the perceived extension of the sidewalk into the ceremonial

main entrance. This five-story glass curtain walled “jewel box” will create an

exceptionally visible and animated grand access. The space will also be used

for informal public recitals and pre-performance chats. Contributing to

an increased level of ambient light, which is presently lacking in the

otherwise dark intersection of University and Queen, the City Room will act as

a glowing glass lantern at night – and an iconic symbol of excellence for the

Canadian performing arts. The Queen Street façade will be more detailed, with

the box office entrance and retail space. The R. Fraser

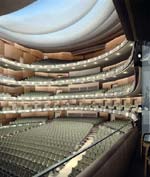

Elliott Hall borrows its classic five-tiered horseshoe shape, complete with

three stages, orchestra pit, and dressing rooms, from traditional European

opera houses. What is most impressive about the interior of the performance

hall is not only its form and elegance, but also the technical care taken

concerning acoustics and sightlines – important to both opera and ballet.

Designed as an isolated structure within the building, the hall offers the

audience unparalleled intimacy with the stage. The absence of the frame, which

usually surrounds a proscenium aperture, allows clear views and a close

connection with the performers – 73 percent of the seats are within a 100-foot

cylinder of center stage. Most of the stage lighting is concealed in layered

plaster “clouds” in the ceiling, which also provide sound reflection. Three

equally sized stages will allow the opera and ballet companies to schedule

performances in repertory. The Four Seasons

Centre is scheduled to open in the summer of 2006. The COC will maintain its

current administrative offices, rehearsal spaces, and workshops at the Joey and

Toby Tanenbaum Opera Centre. I had the opportunity recently to speak with Jack Diamond in his

downtown Toronto office. In addition to expressing his belief that both the art

and science of architecture must fuse to create poetry of form – and getting

beyond the superficial

immediacy of the project’s “wow factor” – he delved deeper into the urban context of the opera house and its

impact on the sociological landscape of downtown Toronto. DSA has created a

structure that speaks volumes of both the present and future of the city. Effie Bouras: Any major challenges inherent in

designing an opera house compared to other cultural venues you have completed? Jack Diamond: In the performing

arts, there is a real distinction between an opera house, a concert hall, and a

theater. A concert hall can essentially be one chamber; a theater has a stage

and an audience chamber (most frequently the pit is a component but it is

tucked under the stage). An opera house is a concert between voice and

instrument, so the pit and the stage are both important and exposed for

acoustic reasons. The pit [for an opera hall] should have the status of an

orchestra in a concert hall; the performance also requires an appropriate

stage. So there are really three components: audience hall, pit, and stage.

There is a considerable back-of-house and it has to be like a factory operating

on split second timing for preparation, delivery, and assembly. Frequently,

there are large casts for opera and ballet, so the dressing room requirements

are also quite considerable. Another characteristic

is the horseshoe plan [which makes] the audience the “decoration” of the room,

so to speak. They envelop the room giving a sense of community and occasion.

Performers like the connection with the audience – to reach out and connect

through the closeness by virtue of the horseshoe shape. Unlike most concert

halls and theaters, we have six levels so there is no deep balcony, which is

acoustically very important. The opera house has no balcony that projects more

than four rows over the audience below, with the last seat in the last row only

overlooking six rows of seats before looking to the stage. Finally, the house

is designed for opera and ballet, making no compromises with respect to sound.

As such, there is no electronic enhancement necessary. There will be electronic

enhancement for jazz or movie festivals, but as a norm there will be a live

orchestra and live performance and absolutely no enhancement. In that respect

it will be like a 19th century opera house. It is a 21st

century house in its design and configuration in general, but in terms of

sound, it will be among the best in the world. EB: What drove the parti of the City Room in terms of aesthetics,

and in what way will the dynamics of the space work for events being held

there? JD: In terms of the

contextual issue, Queen Street is an animated retail street – we have done

likewise by placing the box office, ballet/opera shop, and coffee shop all on

this street. University Avenue is Toronto’s principle boulevard and we have put

the formal address on this avenue with the transparent crystalline box that

makes the audience apparent from the outside. The idea is not to make it

acoustically perfect, as it is here that people can listen to either a

pre-performance talk or a recital. EB: In a sense, it

prepares one for the coming event.

JD: Yes, like a miniature Piazza di Spania [incorporating]

stairs where people can sit [combined] with the glass stairs that serve as circulation

and an open amphitheater. In addition, the plaza encapsulates the sidewalk

outside. Unlike traditional opera houses where there is a flight of steps to

intimidate, this is intended to make the entrance seamless. The rectilinear

aspect of the exterior with the curvilinear contrast of the interior [opera

hall] pays attention to Toronto’s street grid, but it is not a simple filling

out of the block. There are a series of screens: the transparent glass façade,

semi-transparent entrance to the concert hall, then opacity of the concert

hall. There is both the continuation of spaces as well as the definition of

space. This deconstruction of mass gives scale to the building and at the same

time, it is a narrative of its context. EB: Frequently, form and

engineering are developed separately. However, in the opera house these issues

are not mutually exclusive; do you take this approach to design in all of your

work? JD: Good design is making virtues out of necessity. If you can

take a column and make more of it than a structural member, where it separates

space, reflects light, or, as in a Greek temple, it forms the actual elements

of a façade – that is architecture. The highest level of integration is when

the structural, mechanical, electrical, and architectural components are

resolved in the same manner. For example, in the Richmond Hill Library, I split

the columns into clusters of four that carry all of the ductwork. These

clusters became places where the computers for the library are located. I see this

integration as necessary for giving the building its language, rhythms,

grammar, punctuation, and expression. EB: What does the building

of the opera house contribute to Toronto, not only for the opera- and

ballet-going public, but in general? JD: It is a right of passage for Toronto

into an urban center. It is a demonstration that the city has the interest in

and capability of mounting opera, which is a very sophisticated art form. What

Toronto has is this aggregate – streets that are lively and safe, neighborhoods

within the urban core, and intersections of high and mixed density. It is an

extraordinary system not made better by baubles. The best designs are those that resolve opposing

requirements – to be

contextual while maintaining an identity. For example, the opera house has to

be transparent and welcoming, but at the same time have a kernel of

silence in the middle. Project

credits: Architect:

Diamond and Schmitt Architects Incorporated, Toronto Acoustician:

Soundspace Design Ltd., London, U.K. Theater

Planning & Design: Fisher Dachs Associates, New York City Structural

Engineer: Yolles Partnership Inc. Mechanical

Engineer: Crossey Engineering Ltd. Electrical

Engineer: Mulvey + Banani International Inc. Constructor:

PCL Constructors Canada Inc. Project

Management: Stantec Cost

Consultants: Vermeulens Cost Consultants; Clare Randall-Smith & Associates

Limited Associate Acousticians and Sound Systems: Aercoustics Ltd.; Wilson Ihrig Associates; Engineering Harmonics Inc. Fire

& Life Safety: Leber Rubes Traffic

Consultants: BA Group Landscape

Architect: Du Toit Alsop Hillier Established in 1975, Diamond

and Schmitt Architects services include architecture, urban planning,

landscape architecture, building conservation, and interior design. The firm,

with a staff of 112, has received national and international recognition with

more than 90 design awards, including six Governor General’s awards for

architecture. DSA has undertaken projects in Canada, Cuba, Czech Republic,

England, France, Israel, Malaysia, the People’s Republic of China, the United

States, and the West Indies. In 2003, the firm received the Award of Excellence

– Architectural Firm from the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. Effie Bouras, Assoc. AIA, regards architecture as a

multidisciplinary art, an opinion most likely influenced by her multiple

degrees in Civil Engineering and Architecture. She has worked in Las Vegas and

New York City, and is currently writing for various architectural journals. Also featured on ArchNewsNow: Musical

Catalyst: Max M. Fisher Music Center by Diamond and Schmitt Architects The restoration and expansion of historic Detroit Symphony Orchestra Hall sparks downtown redevelopment. |

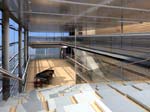

(click on pictures to enlarge)  (AMD for Diamond and Schmitt Architects Inc. (c) 2003) Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts scheduled to open in 2006 (Diamond and Schmitt Architects Inc. (c) 2003) The five-story City Room City Room City Room (Diamond and Schmitt Architects Inc. (c) 2003) The City Room includes space that can be configured as an amphitheater for informal recitals and re-performance talks. (Diamond and Schmitt Architects Inc. (c) 2003) Another view of amphitheater within the City Room (Diamond and Schmitt Architects Inc. (c) 2003) R. Fraser Elliott Hall: view from stage (Diamond and Schmitt Architects Inc. (c) 2003) R. Fraser Elliott Hall: view from box seats (Diamond and Schmitt Architects Inc. © 2003) Early conceptual sketch (Diamond and Schmitt Architects Inc. (c) 2003) Section (Diamond and Schmitt Architects Inc. (c) 2003) Mezzanine plan (Diamond and Schmitt Architects Inc. (c) 2003) Box level plan |

© 2004 ArchNewsNow.com