|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

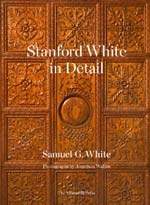

"Stanford White in Detail" by Samuel G. White; photographs by Jonathan Wallen A rich presentation of the sensual and scenographic effects created by the legendary architect. For White, every surface was an opportunity, and few opportunities were neglected. By Samuel G. White, FAIA, LEED AP October 15, 2020 Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from “Stanford White in Detail,” published by The Monacelli Press (October 13, 2020), presented here with permission.

Introduction

… If William Rutherford Mead could be remembered for his success in managing personalities, and Charles Follen McKim for his fidelity to solid forms and a severely classical idiom, nothing defines the work of Stanford White as much as his ornament. Few if any architects before or since could employ decorative motifs with such flair, draw on so great a range of ideas, or achieve a density bordering on saturation without losing control. The effects were dazzling, but the designs can be analyzed in more objective terms, starting with the sources of a decorative vocabulary that spanned from historic precedent to the product of a remarkable imagination.

Stanford White was a classical architect, and his career fits squarely in the 2,500-year classical tradition, but for him the orders were an opportunity rather than an end in themselves. Columns, entablatures, architraves, and pediments were blank canvases awaiting decorative treatment, an attitude that extended to virtually every other surface and feature. From the Greeks he borrowed strigilation, the tight repetition of s-curves based on the tracks of a comb, or strigil, with which Hellenic athletes scraped the oil off their bodies. For him ancient Rome meant the Pantheon, while Byzantium, the successor to the Holy Roman Empire, inspired his mosaics, with the more gold leaf the better. With its celebrations of all things beautiful, the Italian Renaissance became his lodestar and the source for so many of his ideas. He transformed palazzi into gentlemen’s clubs and commercial buildings, filled his interiors with rare marbles, and covered every surface with swirling arabesques. …

Inventing a Vocabulary

In the 1880s, Stanford White and his colleagues responded to the increased opportunities for leisure in post-Civil War America with a new architecture that transformed the resorts along the East Coast. An amalgam of medieval French, English Queen Anne, and 18th-century New England precedents, this idiom was characterized by the architects themselves as “modern colonial,” particularly in its reliance on gable roofs, multi-pane double-hung windows, and discrete classical moldings. Notwithstanding individual precedents, there was nothing revivalist about the work as a whole. In assessing it a century later, noted architectural historian Vincent Scully coined the term “shingle style,” describing the houses as “the architecture of the American summer.”

In parallel to the style’s formal characteristics, White introduced a level of effervescence and energy to the details, as well as a taste for fearless juxtapositions that remain unique in American architecture. The repose of the Short Hills Casino is destabilized by its asymmetrical, nearly weightless entry porch and the surprising unwrapping of the tower’s shingled skin. Medallions of beach pebbles and broken glass, a signature of White’s early work, are set against waves of scalloped shingles in the Newport Casino and houses for Samuel Tilton, Percy Alden, and Robert Goelet. Slender columns of faux bamboo and lithe sea monsters support the weight of Isaac Bell’s wrap-around porch, while Percy Alden’s muscular tower terminates in a calligraphic flourish of metal wire.

White’s interiors are even more innovative, revealing an unbounded, almost limitless imagination. A kaleidoscope of images is connected by a reliance on densely patterned surface textures, unexpected plays of light, shifts of scale, or unusual context. Wood is carved, chased, and polished in every possible direction. For the front hall of Isaac Bell’s Newport house, White fashioned a fireplace alcove out of a medieval French bed, backing the open rosettes with silver foil to create an unexpected source of light. The walls around the stair are clad in over-scaled beaded board, while the walls and ceilings of the dining room are covered in woven cane, with the perforated lids of colonial bed warming pans added for punctuation. The fronts of sideboards are covered in swirling arabesques of tiny upholstery tacks, while hardware, light fixtures, and stained glass in exotic patterns evoke opium-scented passages of Arabian nights. For White, every surface was an opportunity, and few opportunities were neglected.

Experiments

The wave of post-Civil War prosperity generated new building types and institutional programs that were unprecedented in, if not unique to America. Challenges for Stanford White included churches to accommodate a pedagogical agenda as well as a spiritual mission such as Baltimore’s Lovely Lane and New York’s Judson Memorial; Madison Square Garden, an entertainment complex with multiple performance spaces that presented opera on one night, boxing on another; a monumental electrical generating plant for the Interboro Rapid Transit Company; the Bowery Savings Bank, an institution that used architecture to attract and reassure a thrifty clientele; and gentlemen’s clubs for which the character and aspirations of their memberships were reflected in their elevations. Nearly everything White designed was, at some level, an experiment.

To meet the challenge, White employed new materials, new combinations, and new ways of looking at precedents, frequently drawing on European architecture to provide the framework for a solution. The economies of molded terra-cotta ornament allowed him to respect the investors’ budget while presenting the IRT station as a Renaissance palace and to give the Century Association a facade that suggested the spirited intellectual and artistic activities within. The Herald Building, one of White’s best and most original designs, was an ingenious merging of the Torre Orologica in St. Mark’s Square with Verona’s Loggia degli Consiglii, but the design also acknowledged the commercial function of the building with windows under the arcade overlooking the pressroom in the basement. Similarly, the new Tiffany & Co. headquarters was realized as a white marble Venetian palazzo combining muscularity with perfect proportions, while incorporating large show windows for display at street level and industrial steel sash to light the interiors of the modern office building above.

While the interiors of the early houses showed White doing a lot with a little, renovations of two churches demonstrate his virtuosity with expensive materials and his sure hand in combining them. The Church of the Ascension was transformed by a liberal use of Siena marble, mosaics by Maitland Armstrong, bas-relief angels by Louis Saint-Gaudens, and a monumental mural by John La Farge. At St. Paul the Apostle, he tamed the cavernous interior with a majestic half-domed ciborium covered with gilded mosaics that recall the magical interiors of Byzantium.

Samuel G. White, FAIA, LEED AP, a great-grandson of Stanford White, is a consulting partner with New York City-based PBDW Architects. His diverse portfolio of educational, institutional, and residential projects focuses on designs that introduce new interventions to historic settings in ways that both reinforce and reinterpret their contexts. White’s recently completed work includes a new Net-Zero Energy dormitory for the Center for Development Economics at Williams College, expansion of Saint David’s School in New York City, restoration of the cast iron facades of 462 Broadway, and rehabilitation of the historic Bay Head Yacht Club in New Jersey. 462 Broadway, Poly Prep Lower School, and Duane Library have each been recipients of the Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award from the New York Landmarks Conservancy. His current projects include the modernization of Stanford White’s Astor Courts in Rhinebeck, NY. White is the author of The Houses of McKim, Mead & White; McKim, Mead & White: The Masterworks; Stanford White: Architect; and Nice House.

|

(click on pictures to enlarge)  The Monacelli Press “Stanford White in Detail” by Samuel G. White; photographs by Jonathan Wallen; The Monacelli Press, October 2020  Jonathan Wallen Box Hill (Stanford White house), Welsh knot doorknob, Saint James, New York, 1892–1906  Jonathan Wallen Isaac Bell house, Newport, Rhode Island, 1883  Jonathan Wallen Isaac Bell house, Newport Rhode Island, 1883  Jonathan Wallen Newport Casino, Newport, Rhode Island, 1880  Jonathan Wallen Gould Memorial Library, Bronx, New York, 1903  Jonathan Wallen Gould Memorial Library, Bronx, New York, 1903  Jonathan Wallen Players Club, New York, 1889  Jonathan Wallen Century Association, New York, 1889  Jonathan Wallen Judson Memorial Church, New York, 1893  Jonathan Wallen St. Paul the Apostle, New York, 1890  New-York Historical Society Charles Lewis Tiffany house, New York, 1885  Jonathan Wallen Library (stair detail), Seventh Regiment Armory (now Park Avenue Armory), New York, 1880  Jonathan Wallen Library (balcony detail), Seventh Regiment Armory (now Park Avenue Armory), New York, 1880  New-York Historical Society New York Herald Building, New York, 1895  Jonathan Wallen Ionic capital from Madison Square Garden, New York, 1891  Jonathan Wallen Interborough Rapid Transit Company, New York, 1904  Jonathan Wallen Admiral David Glasgow Farragut Monument, Madison Square, New York, 1880  Jonathan Wallen Samuel Tilton house, Newport, Rhode Island, 1882 |

© 2020 ArchNewsNow.com