|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

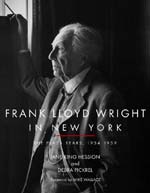

Taliesin East: "Frank Lloyd Wright in New York: The Plaza Years, 1954-1959" by Jane King Hession and Debra Pickrel (Book Excerpt) A Plaza home and office had much to offer the architect, including prestige, prospect, and refuge - an elegant perch from which to survey the city he loved to hate. By Jane King Hession and Debra Pickrel June 8, 2017 Editor’s note: Released in 2007 to coincide with the centennial of New York’s Plaza Hotel, Frank Lloyd Wright in New York: The Plaza Years, 1954-1959 received the 2008 Independent Publisher Awards Gold Medal for Architecture. A 10th anniversary paperback version is being released to coincide with the Museum of Modern Art’s “Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archives” exhibit, opening on June 12.

On its pages, co-authors Jane King Hession and Debra Pickrel examine the momentous five-year period when one of the world's greatest architects and one of the world's greatest cities dynamically coexisted. From his Plaza suite, or "Taliesin East” as it came to be known, Wright supervised construction of the Guggenheim Museum, sparred with the New York press, and received many famous visitors, including Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller.

Featuring a foreword by Mike Wallace of CBS News/60 Minutes fame, whose seminal television interviews of Wright in the 1950s were two of his career favorites, the new version includes a postscript that relays the losses, gains, and alterations to Wright’s New York work in the last decade. The following excerpt is from the book’s introduction.

By the time Frank Lloyd Wright added the Plaza’s address to his official letterhead, he had been traveling to New York for business and pleasure for nearly a half century, but he had always been of two minds about the city. In principle, he abhorred its unrestrained vertical growth, mushrooming population, crowded conditions, and thickening pollution. In practice, however, he enjoyed all that it had to offer. He delighted in strolling midtown’s streets with East Coast friends such as sculptor Isamu Noguchi, browsing favorite Asian art galleries, dining at “21” or other fine Manhattan restaurants, attending the theater (he was fond of musicals), and reading about himself in the New York press. His relationship with the city was both contradictory and complex. As architectural critic Herbert Muschamp discerned, “...an observer might note a discrepancy between the tenor of these remarks and the frequent New York jaunts of their author.” Simply stated, when it came to New York, Wright’s words were one thing, but his actions quite another.

His emotions were not conflicted when it came to the Plaza, however. He had an unabashed affection for the historic building, which he once singled out as “the only beautiful hotel...in all of this god-awful New York.” For decades, he claimed the hotel’s smart restaurants and clubby bars as his own, and favored its comfortable spaces for meetings with friends, business associates, and the press, inviting all of them to “his” domain with the same proprietary phrase: “We will be in New York at the usual place (the Plaza)...” Although Wright proclaimed in The New Yorker in 1952, “I’ve been coming to the Plaza for forty years,” it would be another two years before he became an official resident.

Wright had been visiting the Plaza, a hotel favored by “the smartest names in American society,” for nearly as long as it had been in existence, and it never failed to serve his purposes. In October 1909, the hotel provided sanctuary for the architect and his lover Mamah Borthwick Cheney. After abandoning their families (and his practice) in Oak Park, Illinois, the two stayed at the hotel before setting sail for Europe, where they planned to begin a new life together. During the winter of 1926-27, the Plaza offered reassuring surroundings to the debt-ridden architect when he came to the city to find a buyer for his collection of Japanese prints. With the profits, he hoped to stave off his “ever-threatening creditors” and save Taliesin, his beloved home and studio, from foreclosure. That winter, Wright and cultural critic Lewis Mumford met for the first time at the hotel. Over lunch, the two launched a 30-year association charged with mutual admiration and political differences that often played out in the pages of The New Yorker and other publications. During the 1940s, the architect became familiar with the seductive charms of a Plaza residence as a frequent guest in philanthropist Solomon R. Guggenheim’s luxurious, art-filled rooms, located directly below the ones he would later inhabit. In Guggenheim’s suite, Wright and his wife were “entertained lavishly” as they discussed plans for a new museum of non-objective art that would bear their host’s name and display his extensive collection.

A Plaza home and office had much to offer the architect, including prestige, prospect and refuge – an elegant perch from which to survey the city he loved to hate, and a comfortable haven within which to retreat from its insistent view. Wright’s love of luxury informed his redesign of the Plaza suite, the last home and studio he would create. Throughout his life, regardless of how much he owed his creditors, Wright’s personal quarters were always lavishly appointed. His Plaza suite was no exception: “Wherever he was, for a day or a year, he changed [his rooms] until they pleased his taste,” his sister Maginel Wright Barney noted.

In 1954, Wright issued a press release to announce, or perhaps explain, his opulent accommodations:

He has always worked where he ate and slept and is doing so now with the air of magnificence and expense one associates with the Plaza. He has done the rooms over in the vein of the original Plaza as conceived by Henry Hardenberg (sic) – and managed at the same time to get a practicable working office, show room and sleeping quarters out of it – all pretty harmonious with Plaza elegance – with certain additions Mr. Wright thinks would have pleased Henry Hardenberg (sic), master of German Renaissance.

The effect his metropolitan dwelling had on visitors was not lost on Wright, who possessed an innate gift for self-promotion. He knew the suite, like all his incomparable homes and studios, spoke volumes about its creator. “His own home was his best advertisement, the self-portrait of a man of taste and prestige,” said art historian Julia Meech. ”At mid-century, as he was about to begin construction on Manhattan’s most controversial building, Wright’s posh Plaza suite and fashionable Fifth Avenue address sent precisely the message he intended to convey to New York: the world-famous architect had arrived.

Jane King Hession, a partner in Modern House Productions (Edina, MN), is an architectural writer and historian. A former president of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy, she is the author of several books on Wright and other architects, and co-producer of the documentary Wright on the Park: Saving the City National Bank and Hotel.

Debra Pickrel is founder and principal of Pickrel Communications, Inc. (New York, NY). A former VP of education on the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy board of directors, she also edited its quarterly BULLETIN. Co-author and editor of several architectural history books, she has written for a number of leading design publications including Metropolis, where she is contributing a series of Wright-related posts this summer (past posts include “Remembering Edgar T.” and “Remembering Frank Lloyd Wright’s Demolished Car Showroom”).

|

(click on pictures to enlarge)  Lisa Larsen / Time & Life Pictures / Getty Images On the cover: Frank Lloyd Wright standing at the window of his Plaza suite  Ezra Stoller / Esto Frank Lloyd Wright’s Plaza Hotel suite  Bill Maris / Esto The Plaza Hotel |

© 2017 ArchNewsNow.com