|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

|

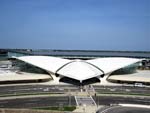

Saarinen's TWA Terminal Revisited It was great to move once again within this swooping, multi-level building with its sunken lounges, suspended bridges, and shallow steps that invite gliding rather than climbing (and that tile work!). By Janet Adams Strong, Ph.D. July 9, 2013 Ever since openhousenewyork (OHNY) was established in 2001, it has offered unique opportunities to experience parts of the built environment not normally open to the public. On Friday, June 21, OHNY upped the ante with a new members’ event in Eero Saarinen’s TWA terminal at Kennedy Airport.

The terminal has been pretty much closed for the last decade following TWA’s bankruptcy in the mid-1990s, the sale of the “Flight Center” to American Airlines, and the subsequent construction of Jet Blue’s new aviation center at its rear. The relatively small “functionally obsolete” terminal was determined inadequate to handle recent security requirements, increased passenger volume, and jumbo jet logistics.

Its useful luster lost, the expressionistic building became a nuisance facility known clinically as Terminal 5. No romantic notions in that. Threatened with demolition, it was saved by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1994. But even after designation, vitality remained an issue as attempts to use the terminal for an exhibition gallery or other repurposing failed.

All of the battles – and the creeping decay that came with abandonment – figured in stark contrast to 1962, when TWA’s innovative terminal opened as the last word in glamorous air travel. Passengers dressed elegantly, not comfortably in sweatpants, for the occasion, and reveled in the experience of flight. Instantly the terminal became a global icon, the most famous aviation building in the world.

Saarinen used concrete and steel, which he maintained were the only true modern materials, to create “a building that would express the drama and specialness and excitement of travel....We wanted the architecture to reveal the terminal, not as a static, enclosed place, but as a place of movement and transition. We wanted an uplift.”

Stories about working in Saarinen’s office for countless hours (TWA claimed more time than any other project), about lying on the floor or standing on tables to build progressively larger, ultimately full-scale models, and about endlessly sketching and refining, refining, refining are the well known lore of Saarinen’s practice.

But now, seeing the terminal with fresh eyes after its painstaking 10-year $20 million restoration by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey in association with Beyer Blinder Belle Architects & Planners, the power of the architecture and the sheer brilliance involved in making it are the arresting focus.

Each view of the compound, incredibly complex curves, all masterfully orchestrated for continuous flow from the smallest detail to the overall building, comes with the almost unbelievable realization that it was all done pre-CATIA, pre-CADD – pre-computer.

It was great to move once again within this swooping, multi-level building with its sunken lounges, suspended bridges, and shallow steps that invite gliding rather than climbing. Center stage are the giant windows onto views of planes lifting off or landing, thrilling now but especially so in the early days of commercial aviation. The experience is heightened by the architecture and brilliantly offset by Charles & Ray Eames’s signature TWA red love seats and the matching red carpet that flows through the tubes to the original gates (now linking Jet Blue’s Terminal 6).

It’s easy to get caught up in the undulating forms and inevitably, in any conversation about the building, that’s the topic enthusiastically discussed. But thanks to OHNY, and lingering rather than rushing to catch a plane, I focused on the fact that virtually the entire interior – walls, floors, stairs, information desk, planters, fountains – almost everything is covered by small circular ceramic tiles.

Most are about a half-inch across, but two smaller discs help to blend the surface into a continuum, like rattlesnake or scaley fish skin or the invisible structure of bone cells revealed. I was briefly reminded of the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama who compulsively duplicates polka dots to create “Infinity Nets.”

The difference is that Terminal 5 is monotonal and the individual dots don’t so much make an obvious pattern as they do structure a coordinated whole wherein the floors, walls, and all other components grow organically from each other. Everything, as Saarinen explained, is part of “a total environment where each part was the consequence of another and all belonged to the same form-world. It is our strong belief that only through such a consistency and such a consequential development can a building make its fullest impact and expression.”

Some four million tiles were used in the restoration campaign alone, in addition to the millions of original custom-made tiles that remained in place. I imagined their installation: most tiles were affixed to net sheets, but many were laid individually by hand in the grout, including the knuckle tiles that angle around the leading edge of each stair. The vision conjured up armies of craftsmen working madly, inch by inch, across the 170,000-square-foot building. Oh, what glorious obsession!

Like most, I was captivated by the information desk/departure board that commands the terminal’s front lobby. Seen straight on, it is balanced and firmly anchored, with clear flight information on a black ground that vaguely suggests some friendly alien visage.

But from every other perspective, the desk races forward like a Futurist sculpture by Umberto Boccioni, no less expressive of movement but more stately, monumental, and more controlled; more architectural.

As I circled around the continuous form I thought of a Kline bottle with no beginning and no end. And then I ventured inside, which was not easy to do. How in the world did TWA’s service personnel begin their day?

There are only two ways in or out: crawling under the open counter (the top is an unhinged marble slab), or my wobbly method without handrails or supports: by climbing over the lowest edge of the enclosure, which is about a foot high and spreads out dimensionally toward the bottom like an angle-less triangle, or wave, before leveling out with the floor.

Either way it’s a physical contest, and certainly would have been in the heels and pencil-straight skirts of 1960s uniforms. Maybe the desk was attended by men who made sport of hurdling over or under? To the degree that such concerns existed, they were secondary to aesthetics. Art above all.

Actually that’s one of the issues facing the terminal’s reuse, specifically in accommodating ADA codes. The current plan to engage the Flight Center as the freestanding public space of two new hotel wings faces a host of challenges.

But who knows? Maybe the terminal will become a destination in itself, a cool place to come for dinner or drinks, or a convenient gathering place for out-of-town guests arriving in New York for a special event, maybe even the place to hold that special event, or a wedding reception, or party. Certainly it would be a great place to spend a few hours waiting for a delayed or canceled flight.

Unfortunately, traffic from outside the airport will likely remain a problem but, like a pilgrimage, the arduous journey promises rich rewards.

Janet Adams Strong, Ph.D., is principal of “Architect Rx, the communications remedy" for the greater A&E industry, and editorial director of Piloti Press, the publishing subsidiary of Architect Rx. |

(click on pictures to enlarge)  Janet Adams Strong Eero Saarinen’s TWA terminal (1962) at Kennedy Airport  Janet Adams Strong Upper level of lobby, view from support spaces  Janet Adams Strong Upper level of lobby, view from mezzanine  Janet Adams Strong Waiting area with Eames seating  Janet Adams Strong Main stairs and handrails  Janet Adams Strong Stair detail  Janet Adams Strong Stair tread detail with safety strips and elongated knuckle tiles that angle around the stair nosing  Janet Adams Strong Seating and stairs to mezzanine  Janet Adams Strong Continuous wall and stair assembly  Janet Adams Strong Curved wall of ceramic tiles  Janet Adams Strong Wall, seating, and mezzanine stairs to waiting area  Janet Adams Strong Freestanding wall terminus on ground floor  Janet Adams Strong Lobby from mezzanine  Janet Adams Strong Information desk/departure board from mezzanine  Janet Adams Strong Information desk/departure board  Janet Adams Strong Information desk/departure board, from rear  Janet Adams Strong Information desk/departure board, raised entrance  Janet Adams Strong Information desk/departure board, from side  Janet Adams Strong Beyer Blinder Belle’s instructional panel for tile restoration  Janet Adams Strong Ladies room |

© 2013 ArchNewsNow.com