|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

|

Krier Answers Weinstein's Questions (and then some!) Dear Mr. Weinstein: Thank you for mentioning my Speer reprint. I will respond gladly to your questions if you respond to my "pointed" questions. By ArchNewsNow July 2, 2013 Editor’s note: On June 18, we posted Norman Weinstein’s op-ed (for lack of a better term), Some Pointed Architectural Queries for Three Connoisseurs of Albert Speer's Monumental Classicism on the Occasion of the Re-publication of "Albert Speer: Architecture 1932-1942" by Leon Krier.

Over the next few days, not only did Krier answer Weinstein’s queries, but a lively debate between the two began. With permission from both (and only slight editing for clarity), we present Krier’s response to Weinstein’s original questions – and the ensuing discussion carried out via e-mail.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

From: Leon Krier Sent: Friday, June 21, 2013 3:31 PM To: Norman Weinstein

Dear Mr. Weinstein,

Thank you for mentioning my Speer reprint. I will respond gladly to your questions if you respond to my "pointed" questions.

– Can a criminal be a great artist?

If you can't deal with that try the following:

– What if Hitler had employed what in your own judgment are great architects, sculptors, painters?

Your tone of writing about Speer and Hitler implies such an occurrence to be an utter impossibility.

I also want to be assured that you will publish my answers whole and unedited, together with your questions.

Best regards

Leon Krier

--------------------------------------------------------------------

From: Norman Weinstein Sent: Saturday, 22 Jun 2013, at 01:55 To: Leon Krier

Dear Mr. Krier,

An essay of mine appeared in a book about the poet Ezra Pound. Was Pound a war criminal? Yes – although not remotely on the scale of Speer. Was he a great poet? Yes I would say – at various points in his career.

So that was a simple question to answer. Yes, I think a criminal can be a great artist. Some have been.

But you build a case for Speer being a great architect. I believe that the practice of architecture needs to constantly address ethical professional conduct. Any architect who acts as if a code of professional conduct is tangential to the profession I can not consider great. And since medicine, like architecture, represents a fusion of art and science framed within a code of professional ethical conduct, I also don't consider Speer's contemporary, Dr. Mengele, to have been a great physician and medical researcher. My opinion about a great architect being bound to a rational code of ethical professional behavior for the common good of his/her community is clearly not exclusively my opinion. Doesn't Vitruvius remind us of this ethical responsibility of the architect in his Ten Books on Architecture? I could cite other examples across cultures and eras of the crucial interface between architectural practice (great or ordinary) and ethical professional conduct – but I await hearing more of your thinking about how architectural greatness exemplified by Speer transcends some or all professional ethical considerations. Or do I misunderstand your thinking about this?

I am cc'ing this e-mail to my editor with the hope that she publishes both your important questions in this note, and your forthcoming detailed answers.

Thank you for your prompt response.

Sincerely,

Norman Weinstein

--------------------------------------------------------------------

From: Leon Krier Sent: Saturday, June 22, 2013 11:04:02 CEST To: Norman Weinstein

Dear Mr. Weinstein,

I also greatly appreciate your responding directly. 27 years ago I was not given the chance to respond to unilateral accusation. Robert Stern is protecting me from the unjustifiable accusations of philo-Nazism. In that, I am profoundly indebted to him because he allows a debate to happen, which has been suppressed for three generations.

Looking forward to our exchange. If you can prove an error in my line of argument I am glad to correct.

Sincerely,

Leon Krier

--------------------------------------------------------------------

From: Leon Krier Subject: Q&A Date: 23 June 2013 17:44:46 CEST To: Norman Weinstein

Dear Mr. Weinstein,

Here are my answers to your questions. I would, of course, be happy if your editor made them public.

Kindly let me know.

Best regards,

Leon Krier

[attachment]:

Some questions for author Leon Krier:

Norman Weinstein: You refer to Nazi architect Albert Speer as “a born-form giver.” Could you please define this phrase? Does it suggest a genetic predisposition for design?

Leon Krier: Mental and physical abilities are inborn – an athlete, a pianist, a logician have a “genetic predisposition” to do with ease what others can only do with difficulty or not at all. Talents, intelligence, manuality, or intellectuality are not evenly distributed. That is the foundation of the diversity of human skills, crafts, professions. A high gift in one of the human abilities may be paired with a tragic deficiency in another. Intelligence in one field may be hampered by a tragic disability in another field. A great object designer like Le Corbusier was a miserable urbanist. Speer was an exceptional form-giver, equally gifted in designing a piece of furniture, a building of domestic or monumental scale, or a metropolis. I say exceptional because none of the skills he deployed in a very short period of time were taught at the time he studied with or was assistant to Professor Heinrich Tessenow at the Polytechnic in Berlin. In other words, he was an autodidact in classical architecture.

NW: How would you briefly summarize your sense of how successfully Speer fulfilled his professional obligations for a design-driven dialogue with Hitler?

LK: There is no doubt in my mind that Hitler had solid architectural judgment – his sketches are not those of an amateur. To go on pretending that he was just a failed artist is disproven by the “Hitler’s Architekten” scientific research project conducted in parallel by Professors Winfried Nerdinger and Raphael Rosenberg at the Universities of Munich and Vienna. Under his direct influence, Hitler’s first architect, Paul Ludwig Troost, developed an austere minimalist classicism, which was principally influenced by Otto Wagner. Speer developed that style and expanded it with the increasing size and ambition of his architectural and urban projects. The architects he employed had, just like him, been trained only in a vernacular or a modernist design-discipline at Stuttgart, Munich, or Berlin, in Weimar and Dessau. Only the generation of Peter Behrens, Paul Bonatz, Ludwig Ruff, and Wilhelm Kreis had been trained in the Beaux Arts manner. According to Speer, the lack of classical design skills of young architects became critical when confronted with the large commissions of the regime. In 1938, he organized an internal competition called “Die Reiche Fassade,” or “the richly adorned façade,” in order to ensure the architectural variety for the North South Axis, intended to rival Paris avenues. Hitler had less understanding of urbanism. Speer, under the influence of O. Wagner’s Plan for Vienna and Saarinen’s Plan for Helsinki, developed a uniquely visionary master plan for a modern metropolis well beyond Hitler’s assignment and expectations. This then served as a model for the later plans for Munich, Hamburg, Linz, etc.

NW: Should his architectural career in any way take into consideration his preference for using forced labor teams to realize his designs?

LK: Like Hitler, Speer and so many of his contemporaries suffered a blinding hubris of imperial scale. In them, the romantic hero model mutated into the genocidal criminal. The racist policies of the regime had been given a modern (pseudo) scientific base, allowing the criminals to act in good conscience and with unbending determination, best described in Jonathan Littell’s novel, The Kindly Ones (Les Bienveillants).

By December 1941, it was clear that Germany could not win the war. The collective engagement of the Wehrmacht in genocidal crime, which started with the invasion of Poland, allowed no turn-about even for the most lucid Nazis (forced labor was but one facet of that crime). It meant that from now on there was no turning back – there was only a dumb forward march into the Endlösung (Final Destruction of the Jews), and equally into German self destruction.

NW: Was Speer’s first substantial independent job as “Commissioner for the Artistic and Technical Presentation of Party Rallies and Demonstrates” an ideal preparation for the development of his classical monumental architectural style?

LK: Speer was an extremely quick learner combined with great ambition, artistic judgment, and organizational skill. As is demonstrated by the architectural publications he was responsible for, the magazine Kunst im Dritten Reich [Art in the Third Reich], and books likes Die Neue Deutsche Baukunst [New German Art of Architecture], this judgment was embracing classical, vernacular, and modernist building styles and methods, temporary and permanent buildings for all branches of Nazi society.

NW: How might you have experienced the architectural grandeur of the Zeppelinfeld [Zeppelin Field] at night, the time Speer most wanted the stadium inhabited?

LK: I have personally never experienced nor do I have any inclination to experience mass meetings of any kind or regime. The spectacular Lichtdom [Cathedral of Light] you refer too was inspired by illuminations for preceding world exhibitions by artists like Granet, Melnikow, and Lubetkin.

NW: What do you think might have prompted Speer’s father, responding to his son’s model for the three-mile wide Prachtallee (Boulevard of Dreams), to day “You’ve all gone completely insane.”

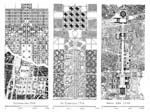

LK: Pracht-Allee means Grand Avenue or Avenue of Splendor. Your naming “Boulevard of Dreams” would be translated as Traum-Allee. You mean, no doubt, 3-mile-long, not wide. The said avenue was comprised of two segments: one of 160 x 3,000 meters, and one of 300 x 1,000 meters. See the scale comparison of the North-South Axis of Speer and Le Corbusier’s plan of a 3-million Metropolis as applied to central Paris 1922 and Ville Radieuse 1933 projects [pictured right]. Speer’s father was right. His “all gone mad” not only indicts the insanity of his son, but equally that of Hilberseimer’s Berlin Hochschulstadt [University City] competition of 1937 (!), or that of Le Corbusier’s contemporary attacks on Paris or Algiers.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

From: Norman Weinstein Sent: Sunday, June 23, 2013 00:13 AM To: Leon Krier

Dear Mr. Krier,

I do not understand why you think Albert Speer was a great architect. Your argument for Speer only begins to make any sense if the practice of architecture should be judged as a purely aesthetic affair having no necessary connection to the practice of common human decency. I have already clearly stated my position in that regard. We have very different definitions of the ethical responsibilities of a professional architect. Since we do, I could hardly hope to show you your error because you seem to believe that architectural aesthetics and ethical professional architectural practice are totally unrelated concerns. Your belief is what it is. That is quite different from a flaw in your logical reasoning.

Your inability to understand the intensity of opposition to your adoration of Speer as architect I find puzzling. As I pointed out in my last e-mail, by bifurcating aesthetics from ethical practice in architecture, you are setting yourself apart from centuries of architecture practice where ethical conduct and design intelligence have been integrally linked. Additionally, I cannot understand how you thought the first edition of your Speer book would have been more uncritically received. Speer's crimes against humanity make him no ordinary figure in the history of architecture. The Reich Chancellery was no ordinary building – and to pretend otherwise and treat it divorced from its function in the Third Reich I find repugnant. But that is your belief – that it was a thing of beauty as architecture – and nothing else about the building matters but your perception of its beauty. I cannot expect to change your opinion.

I would strongly suggest that since you feel you have been wronged by the charges of philo-Nazism, you could consider the bold step of giving part of your book royalties to humanitarian organizations that are still undoing the damage created by those who must have appreciated working in what they perceived as the beautiful Reich Chancellery.

Frankly, I have no need for ongoing email exchanges with you about this matter. I hope my editor will print your answers to my queries. Based on her decision, I will decide whether to continue to engage with you in what increasingly, from my perspective, is moving into a dead-end. For all your complaints about unjust treatment for your thinking about Speer, you have received an extraordinary amount of public attention, and the opportunity to teach and give public lectures at the Yale School of Architecture. While your writing has made you controversial and subject to scorn from various quarters, it seems to me to have also aided your career. Although Mr. Stern is happy to do that, I am not. So whether I again write to you will hinge on whether I think the contemporary practice of architecture itself will gain from the airing of our differences publicly beyond your answers to my queries in ArchNewsNow. I trust that if I decide not to respond to you in the future, you will understand that that does not imply an inability to do so. It reflects my desire to preserve my energy and refrain from attempting to reason with anyone enchanted by his own dogmatic belief.

Sincerely,

Norman Weinstein

--------------------------------------------------------------------

From: Leon Krier Sent: Sunday, June 23, 2013 3:16 AM To: Norman Weinstein

Dear Mr. Weinstein,

Now that it is getting interesting you want to throw in the towel.

Do you also condemn on ethical grounds the techniques and aesthetics of the buildings [pictured at right]? Do you tell architects, students that they cannot, must not, will not design in this manner, with those materials, building types, composition methods, construction methods, and proportions because they were produced in the Third Reich, by engaged Nazi architects for Nazi industries? If you do, you should proclaim it on your public platform and also, by the way, put into question the moral standards of those architects, clients, users, and teachers who proclaim that this kind of architecture is unpolluted by Nazi abuse. If you do not, how can you not be ashamed of yourself, of your double standards and your beliefs?

Sincerely,

Leon Krier

PS Kindly put your editor in the loop.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

From: Norman Weinstein Sent: Sunday, June 23, 2013 8:04 PM To: Leon Krier

Dear Mr. Krier,

Thank you for your responses that are being forwarded to my editor. My responses are as follows – and include responses to your additional note today with photographs.

I respect your architectural knowledge – but believe you are on weak ground as a geneticist. If your answer was meant to imply that one can be a “born architect,” the entire worldwide enterprise of architectural education will have to drastically change admission standards and curriculum. Speer may have been an exceptional form-giver, but perhaps more in his role as Minister of Armaments than as an architect. How does an architect give form to genocidal world conquest? How do you judge the architectural aesthetics of the Reich Chancellery? How successfully did it operate as a think-tank for the extermination of millions? How might a Post-Occupancy Evaluation have been conducted? By how well caked blood could be removed from walls? Was its classical minimalism fitting for a nerve-center of a psychopath’s seat of delusionary world power? Or better yet, since you believe that Hitler possessed “solid architectural skills . . . his sketches are not those of an amateur,” do you judge the Reich Chancellery as a dazzling architectural achievement worthy of Hitler, the would-be architectural talent the world failed to acknowledge? How curious, then, that Hitler was repeatedly denied admission to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Perhaps the admission committee failed to recognize “a born form-giver” when they saw one?

You cite two professors who have “proven” Hitler’s artistic talent. Did they also prove the wrong judgment of the Vienna Arts Academy in not accepting Hitler as a promising student? How did they “prove” it? Is authentic artistic talent established through DNA sampling? On the other hand, here’s a quote from the internationally respected contemporary German art historian Adrian von Buttlar from his article entitled “’Germanic’ Structure versus ‘American’ Texture” (German Historical Institute, GHI Bulletin Supplement 2 (2005), p. 68). Buttlar writes:

“Albert Speer, in his memoirs, saw himself as a successor to [Friedrich] Gilly and Karl Frederick Schinkel, from whom he borrowed several motifs and details – abstracted, of course, from their structural context and human scale. He also pitied himself because Hitler, an admirer of Vienna’s Ringstrasse, had no sense for Prussian virtues in architecture. For Speer, Hitler’s demands led him down a false path toward gargantuan splendor and historicist eclecticism.”

The fact that Speer was an autodidact in classical architecture does not seem to be a cogent fact. Many architects of different quality in a variety of styles have been autodidacts. I find most moving Speer’s recognition of his own limitations as an architect and urban planner in misjudging proportion. Could not such a lack have been a consequence of overreliance upon autodidacticism? But Buttlar raises the possibility that Hitler might not have been as gifted in architectural thinking as you believe, either. And Buttlar’s analysis might also suggest that what you consider Speer’s majestic modern classical architectural style was perhaps a crude pastiche, drawing inspiration whenever possible from Gilly’s and Schinkel’s designs?

BTW, since you appreciate Paul Ludwig Troost’s architecture, please explain how his Ehrentempel [Honor Temples, or Temples for the National Socialist Martyrs, picture at right] effectively functioned as great monumental public art rather than faux Greco-Roman kitsch. Of course, Hitler wanted to re-write architectural history so that Roman temple architecture was actually a “steal” from Nordic vernacular. So why be surprised that Troost was along for the ride? Wasn’t Speer also willing to go along with Hitler’s desire to re-write architectural history as a chronicle of the achievements of the “superior race?”

Finally, whatever Le Corbusier’s failures as an urban planner, I cannot recall him using his design knowledge to help exterminate Jews in order to have his ideal city plan realized. Speer’s Berlin plans did entail taking homes away from Jews whose displacement could be handled, as it typically was, by dispatching displaced home owners to concentration camps. To try to imagine that Speer’s father had anyone else in mind – let alone Le Corbusier – when he addressed the planning insanity of his son seems silly. You are not the first to attribute an authoritarian mind-set to Le Corbusier – but you may be the first to try to establish equal guilt for an architect with an occasional totalitarian mind-set and an architect who knowingly designed to catalyze actual genocide.

After all this, I don’t believe that you have actually answered my queries about the interface of the architecture practice of Albert Speer and the ethical obligations historically integral to the title of professional architect. The question of whether or not I would ethically condemn the buildings illustrated, you have divided into an analysis of two categories: techniques and aesthetics. This is a clever debate tactic – but nothing more. To answer your query as you framed it – bifurcating the aesthetic appeal of architecture from the techniques used to produce it, or the subsequent use of the architecture after completion – would be to accept the validity of your assumption that architectural aesthetics and the ethics of architects are totally unrelated realities. I don’t. I condemn any contemporary architect who would operate with the professional ethics of Albert Speer. Historian Gitta Sereny, in The Healing Wound: Experiences and Reflections, Germany, 1938-2001 (2001), writes that Speer had at his command a workforce of 28 million, of which 6 million were forcibly imported from conquered countries and 60,000 were concentration camp prisoners.

You extend your penchant for bifurcating aesthetics from ethical professional practice by attaching a need to supposedly link an ethical judgment to architectural materials themselves. Do I find Speer’s use of stone unethical? I do not believe that stone in and of itself can earn an ethical designation. That is why architects are bound to a professional code of ethics. It is how and why they design architecture with materials – and not the materials themselves in most cases – that establish ethical judgment. I would make an exception for any architect who would use human remains as building material. Do you believe that Albert Speer would not stoop to that level of moral depravity? Would you consider that he might have regularly used for daily cleansing a soap bar that once was a living Jew?

Now, in order to clear Speer of his complicity in designing architecture used for the purpose of mass murder, I note how you want to clear his “good name” by making his moral equivalents (or even inferiors) current architects using non-sustainable materials. But to buy into your comparison would make an architect committed to genocide the moral equivalent of an architect using non-sustainable materials in order to design a children’s cancer treatment center or hospice. Is that what you believe?

BTW, unlike you, I don’t have any prestigious public platform, nor do I earn income for writing about architecture for ArchNewNow. I also don’t teach architects. My work entails teaching students to read classic literature and examine great art on as many levels of critical analysis as they can responsibly and critically sustain. I am not in the business of telling architects what they can or should design in our time. We work in very different professional circles. But let me give an architect the floor as I close. A noteworthy U.K. architect, David Farrow, wrote more compellingly in response to your assessment of Albert Speer’s architectural stature than I believe I ever could:

Of course, I write as someone who lost seven members of my mother's family to a V-bomb built by Speer's slave labourers, but that's not the reason I find his designs simplistic, inelegant, bombastic and crass.

My conversation with you, in any form, I will now gratefully and formally end.

Sincerely,

Norman Weinstein

--------------------------------------------------------------------

From: Leon Krier Sent: Monday, June 24, 2013 2:01 AM To: Norman Weinstein

Dear Mr Weinstein,

You keep implying erroneously that I approve of Speer's ethics because I do not condemn his architecture and urbanism. That is a mistake. If mistakes are not corrected they become lies.

You do not need to be a geneticist to know that humans are born with specific gifts and that no amount of education can compensate for a basic lack of talent, be it in the field of the arts, science, humanities, sports, or of any human activity.

The industrial buildings illustrated were designed, built, and used to build Nazi killing machines. According to your deontological ethics, that purpose disqualifies and pollutes irreversibly their architecture? Had their architects and engineers, Rimpl and Kohlbecker and Schupp and Kemmer and so many others, realized the Chancellery in Berlin and the temples on the Koenigsplatz in Munich, with the techniques and aesthetics and labor force they used for building Nazi factories, do you seriously believe that that abuse of modernism for Nazi purposes would have killed the chances of modernism for the post-WWII period? If you do, you should be writing about this, make it public and have it debated.

You know very little about the modern architectural publishing world to believe that I am earning money by editing a book on Speer's architecture.

If you want to end our conversation here, I hope you will not discourage your editor from publishing it.

Best regards,

Leon Krier

--------------------------------------------------------------------

From: Leon Krier Sent: Tuesday, June 25, 2013 8:29 AM To: Norman Weinstein

Dear Mr. Weinstein,

Have you heard whether your editor is publishing my responses to your Questions?

I am glad to say that Architectural Review will publish today my response to Joseph Rykwert's column. Do you think that is a turn for the better or the worse?

Best regards,

Leon Krier

PS I keenly await your comments on your assessment of the architectural value of the Volkswagen and Heinkel factories [pictured at right]. Would you term it good or bad modernism? As far as modernisms go, I don't think Mies or Hilberseimer could have done it better. They were still in Berlin when these were built, awaiting appointments from Nazi gangsters.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

From: Norman Weinstein Tuesday, 25 Jun 2013, at 17:02 To: Leon Krier

Dear Mr. Krier,

I believe that my editor will be in touch with you in the next few days. You are welcome to contact her yourself, if you wish, before the end of this week. She is cc'ed on this e-mail.

I have repeatedly made clear to you that I do not see the issue of Speer's stylistic choice as the gist of our difference. That Modernism and other architectural styles have been used insensitively and in the service of inhumanity I have always acknowledged. The buildings you are dying to know my opinion of strike me as trashy vulgarizations of Modernism. But I think you may be aware – perhaps my hope is naïve? – that this has nothing to do with the gist of our differing view of the specific meaning and value of Speer's architecture. You chose to specifically valorize Speer as a master of monumental neo-classicism. This is not some vaguely general, purely academic debate about the pluses and minuses of "Neo-Classicism" vs. “Modernism" – and I am exhausted by your dogmatic attempts to re-frame our differences that way. Stand by your book's specific subject. I addressed what followed from your choice of Speer as great neo-classical architect – and also made clear that I see no purpose in continuing a debate with you beyond the very lengthy one that Kristen Richards intends to publish. Out of common courtesy, I want my wish respected by you from this moment on.

Sincerely,

Norman Weinstein

--------------------------------------------------------------------

From: Leon Krier Sent: Tuesday, June 25, 2013 9:47 AM To: Norman Weinstein

Thank you Mr Weinstein,

Your will be done.

I await Ms. Richards’ communication.

Sincerely,

Leon Krier

|

(click on pictures to enlarge)  Courtesy of Leon Krier (left): Le Corbusier Ville pour 3 million d'habitants, 1922, from Oeuvre completes 1910-1929, combined with Le Corbusier Plan voisin for Paris, 1922; figure ground plan from Beziehungen by Tomas Valena, Ernst and Sohn, Berlin, 1994; (center): Le Corbusier La ville Radieuse, 1933, from La ville Radieuse, 1933; (right): From Albert Speer: Architecture 1932-42, ed. Leon Krier, AAM Editions, 1985, Reprint Monacelli, 2013.  Illustration from Kunst im Dritten Reich, February 1940, Ausgabe B – Die Baukunst Herbert Rimpl: Gasstation and Heinkel Aviation Factory, Oranienburg, Germany, 1934-1936  i.A. K. Kohlbecker Karl Kohlbecker: Haus der Sauberkeit, Gaggenau, 1934  i.A. K. Kohlbecker Karl Kohlbecker: Volkswagenwerk, Wolfsburg, 1939  Frau Prof. Gerdy Troost, Das Bauen im neuen Reich, Vol. 1, Bayreuth, 1938, via thirdreichruins.com Paul Ludwig Troost: Ehrentempel / Temple for the National Socialist Martyrs (1933–36), Königsplatz, Munich. |

© 2013 ArchNewsNow.com