|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

|

Overdrive: L.A.'s Future is Present in its Past Simultaneously hopeful and wistful, The Getty Museum's exhibition is about the evolution of a modern city seen through its architecture, confirming the truly layered nature of Los Angeles. By Julie D. Taylor April 19, 2013 “Overdrive: L.A. Constructs the Future, 1940–1990” (through July 21st) at The Getty Center in Los Angeles is not so much an exhibition of L.A.’s modern architecture as it is about the evolution of L.A. as a modern city seen through architecture. Make sense? It does when you see this impressive collection of drawings, models, photos, ephemera, and videos organized into five sections that define characteristics of this innovative and complex city: Car Culture, Urban Networks, Engines of Innovation, Community Magnets, and Residential Fabric. According to Jim Cuno, president/CEO of the Getty Trust, the show confirms that “in addition to houses by Ray Kappe, Pierre Koenig, and Richard Neutra, L.A.’s modern architecture also comprises freeways, coffee shops, trailers, and Disneyland.” Serious Modernist principles mix with fun and pleasure, confirming the truly layered nature of Los Angeles.

This exhibition is part of “Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Architecture in LA,” which The Getty has mounted along with many partner organizations. This follows a similar format to the incredibly successful 2011–2012 “Pacific Standard Time: Art in LA, 1945–1980,” which means for the next few months, Southern California is bursting with exhibitions, events, tours, and talks. (See www.pacificstandardtimepresents.org for full schedules.)

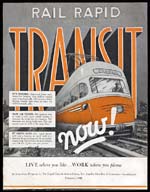

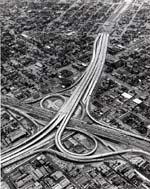

“Overdrive,” as an opinionated survey of L.A.’s essence, is simultaneously hopeful and wistful. There is optimism in plans for public transportation, the jet-age future, and utopian living. Yet there is also the feeling of lost time and squandered opportunities. Ideas for public transportation and social housing are almost poised as memento mori. Hanging high above exhibits of freeway plans and scuttled public transportation efforts is a poster of Disneyland’s Autopia that is almost a jeering reminder of utopia never found.

In contrast, it is gratifying to see the elevation of L.A.’s vernacular architecture – once considered lowbrow (why preserve a diner?) – to museum-quality stature, confirming a new level of scholarly appreciation and attention. This approach is emphasized immediately in the opening Car Culture section that features car-accessed architecture: gas stations, strip malls, and “Googie” diners. Freeways and boulevards are saved for Urban Networks, which surveys transportation and power that mark the city. Construction photos of the LAX Theme Building are particularly delightful, and representative of the many hidden gems the curators found in numerous international archives. The audio/video component (most of which is available online) comprises short films on specific topics, such as Bunker Hill, Capitol Records, and the L.A. River, as well as oral histories with photographer Julius Shulman, architect David C. Martin, and architecture publicist Martin Brower, among others.

Focusing on the industries that shaped the modern metropolis – oil, aerospace, commerce, media – Engines of Innovation gives Corporate Modernism (one of my favorite architectural expressions) its due. The Corporate Modernists (AC Martin & Associates, Welton Becket & Associates, Pereira & Luckman), whose work has been too often ignored or maligned in critical circles, are shown to be as important as the often cited auteurs of L.A. The rise of media and the creative classes in the 1990s heralded a new corporate architecture – epitomized by Frank O. Gehry’s Chiat/Day headquarters – that continues to be driven by the auteur generations of architects.

The last two sections not only encapsulate the soul of L.A. design, but also show elements that are often exported, such as entertainment and residential architecture. Community Magnets is really about centers for entertainment, sport, shopping, and culture. At first blush, I thought it odd that Dodger Stadium, Getty Villa, and The Music Center were shown as examples of “community,” which, to me, connotes a more organic construct. But considering that the sprawling terrain of the city necessitates Angelenos take a 20-minute drive and spend 10 more searching for parking so that we may stroll a few blocks and commune with others, these are the places where we find community.

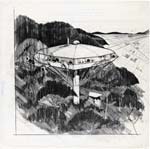

Curators Wim de Wit, Christopher James Alexander, and Rani Singh place their paean to residential architecture in the final section. In Residential Fabric, the span of the show – 1940 to 1990 – is most fully engaged. “Many of the housing experiments that appeared after World War II were actually conceived before the war ended,” notes de Wit. “But they couldn’t be realized until afterward because of material availability.” The Park La Brea housing complex, the suburb of Lakewood, and L.A.’s “dingbat” apartments take their places among legendary Modern single-family homes. The more recent houses (shown mainly through large models by Gehry, Eric Owen Moss, Thom Mayne, and Michael Rotondi) represent the culmination of themes set forth in the prior rooms.

This rich and impressive exhibition succeeds in conveying the history and heart of modern Los Angeles through the eyes of its architects. It will be interesting to see how this plays nationally when it goes to the National Building Museum in Washington, DC (October 13, 2013–March 2, 2014). Even as a local booster, the show doesn’t shy away from controversial aspects of L.A.’s growth, making it an honest – and loving – portrait of the city.

Julie D. Taylor is West Coast correspondent for ArchNewsNow.com, editor of Society of Architectural Historians/SCC News, and principal of Taylor & Company public relations and marketing for the design industries.

|

(click on pictures to enlarge)  ©Luckman Salas O’Brien; Alan E. Leib Collection LAX Theme Building by Pereira & Luckman, Welton Becket & Associates, and Paul R. Williams, 1958.  Langdon Wilson International Getty Villa by Langdon Wilson Architects and Norman Neuerburg, 1971–1974.  Diniz Family Archive; Edward Cella Art and Architecture Century Plaza Hotel by Minoru Yamasaki, 1962, in a screenprint by Carlos Diniz.  ©J. Paul Getty Trust. Used with permission. Julius Shulman Photography Archive, Research Library at the Getty Research Institute Department of Water and Power Building by A.C. Martin & Associates, 1964, in a photograph by Julius Shulman.  ©J. Paul Getty Trust; The Getty Research Institute Dorothy Chandler Pavilion by Welton Becket & Associates, c. 1960.  Armet Davis Newlove Architects Romeo’s Times Square Restaurant by Armet & Davis, 1955.  Jeffrey Daniels Architects Kentucky Fried Chicken by Grinstein/Daniels Inc.,1990.  Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Library & Archive Rail Rapid Transit Now! by Rapid Transit Action Group, Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, 1948.  Automobile Club of Southern California Archives Santa Monica Freeway (Interstate 10) and Harbor Freeway (Interstate 110) Interchange, May 1962, in a photograph by Dave Packwood.  ©The John Lautner Foundation; The John Lautner Archive, Research Library at the Getty Research Institute The Chemosphere by John Lautner, 1960.  ©Rapson Architects; Gregory Ain Papers, Architecture & Design Collection, Art, Design & Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara Case Study House #4 by Ralph Rapson, 1945.  Raphael Soriano Collection, ENV Archives-Special Collections, Cal Poly Pomona Apartment house for Lucille Colby by Raphael S. Soriano, 1949.  Collection of L.J. Cella Art Center campus by Craig Ellwood Associates, 1976, in a drawing by Carlos Diniz. |

© 2013 ArchNewsNow.com