|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

|

Book Review: The Architecture of Patterns, by Paul Andersen and David Salomon A new book considers how the Modernist adage "form follows function" has stuck around in a whole new guise. By Ann Lui October 22, 2010 Lately, it’s not hard to see patterns in architecture. Not trends or styles – though there’s also certainly that too – but literal patterns. Gone are the stark, bare walls of Modernism. Unadorned concrete has been replaced everywhere by skins: colorful, plain, metallic, folded or perforated. From the tiny pinholes on Herzog & de Meuron’s De Young Museum façade; to hundreds of small circular reflectors on the new Santa Monica Bloomingdale’s, formal repetition, it seems, is the newest Big Thing.

Paul Andersen and David Salomon’s new book The Architecture of Patterns (W.W. Norton, October 2010) investigates how, ironically, these architectural patterns have become a pattern themselves.

At first look, this trend might seem like a techy revival of the pre-Miesian days – Victorian houses covered in decorative frosting, Louis XIV gilt and fuss, an era when decoration ruled supreme. The façade of Herzog & de Meuron’s Prada Aoyama in Tokyo, for example, might seem like expensive adornment. However, for this case and many others, The Architecture of Patterns considers how the Modernist adage “form follows function” has stuck around in a whole new guise.

Andersen and Salomon explore how architects have begun to use patterns – biological, geological, urban, and cultural – to redefine both the words “form” and “function.” They juxtapose a number of notable recent buildings with non-architectural patterns to illustrate relationships. For example: structural systems in microscopic cell walls function similarly to the architectural “diagrid” system. Other patterns in cultural artifacts offer insight into the way people live: symmetry in Peruvian weaving, for example, reflects the way in which it is created by two people sitting opposite from one another. The authors believe that patterns combine the utilitarian qualities of Modernism with the culturally specific and more flexible tenets of post-Modernism.

“A new understanding of architectural patterns,” the book reads, “maintains the emphasis on performance and aesthetic coherence found in Modernism, while incorporating the indexicality, hybridity, and ambiguity of post-Modernism.”

Patterns takes on a major project: the authors define patterns as anything that repeats according to some sort of logic, including examples such as a waffle iron, the sole of a shoe, steel structures, fashion trends, and even the human genome. To compound the problem, new technology is allowing architects to more deeply mine patterns that they see in everyday life, all over the world. From this perspective, the project of analyzing patterns – multifarious and ubiquitous – seems almost impossible. Where does it stop?

Sometimes the authors don’t even know. While the book revolves around a few case studies, Andersen and Solomon also frequently find themselves in the midst of highly-specific tangents. Obsessed with patterns of all types, this book’s strength and weakness lie in this research. For example, passages about “plurality” or “dynamic instability” of all patterns without any qualitative examples are hard to follow.

On the other hand, the authors’ frequent repetition of the idea that architecture is – at its heart – the synthesis of many patterns of “spatial and temporal demands, integrating material and social behaviors and combining cultural trends [and] formal desires” is profound. They suggest that the reason that architects have become so attracted to formal patterns is that patterns are, in various forms, the ingredients of an architect’s work.

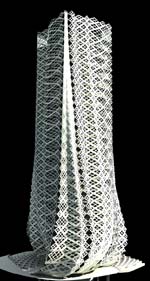

The architectural case studies mostly deal with patterns in façade systems (even if those patterns also have structural or functional properties). Herzog & de Meuron’s Prada Aoyama is given a lot of attention, as well as the O-14 tower in Dubai by Reiser + Umemoto; Gnuform’s proposal for the P.S.1 courtyard; FOA/Foreign Office Architects’ John Lewis Department Store in Leicester, U.K.; and works by BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group). Perhaps the reason that Patterns only has examples of patterns used in one-dimension is that the industry has yet to use patterns as rigorously in organizational systems, landscape, or urban planning.

Similarly, the cultural and historic diversity of non-architectural examples is enjoyable and enlightening: the authors speak as articulately about Peruvian weavings as they do about chemistry and Pop Art. The buildings presented, however, do not feel as diverse. Notably missing are case studies of vernacular architecture, surely a source of many patterns, which would have been fitting to the thesis that all building is a project of patterns.

Recently, a Tokyo study was investigating a common fungus – Physarum polycephalum. This fungus has seemingly random pseudopods that are used to gather nutrients as part of the fungus’s life strategy, branching leg-like appendages reaching out in all directions. Scientists found that when they superimposed an image of this fungus over a map of the Tokyo subway – the pattern matched. The subway and the fungus both had developed in a way that was providing maximum gain to cost – at wildly different scales.

The Architecture of Patterns draws a link between natural, biological, and cultural patterns, and patterns in the built world. After reading it, you’ll begin a pattern of your own: seeing patterns everywhere. The book suggests that patterns – an idea too big to be indexed or understood by any text – can provide unexpected order and meaning to architecture, innovating our ideas of both form and function.

Ann Lui is a fifth-year student of architecture at Cornell University. She is a former Arts & Entertainment Editor of the Cornell Daily Sun, where she continues to write the column “Paper Architect” about issues related to the design field, academia, and general pop culture. Thoroughly afflicted with wander lust, Ann has lived in San Francisco, Buenos Aires, and Rome, and is currently working on a novel in Chicago. She can be reached at all48@cornell.edu.

Also by Ann Lui:

Veni, Vidi, Vici: Museo MAXXI by Zaha Hadid Architects Rome, Italy: The ancient city's newest museum is a reminder that here is a woman at the top of the field - and a testament to the fact that women build, and build well. |

(click on pictures to enlarge)

Naoki Sugibayashi Herzog & de Meuron: Prada Aoyama, Tokyo (2003)  Herzog & de Meuron Prada Aoyama: unfolded elevation showing different panel uses  Satoru Mishima Foreign Office Architects: John Lewis Department Store, Leicester, U.K. (2008)  Valerie Bennett John Lewis Department Store interior detail  Foreign Office Architects John Lewis Department Store: unfolded elevation showing different tile types  Foreign Office Architects John Lewis Department Store: examples of different tile configurations  Atelier Manferdini Atelier Manferdini: laser cut dress  Atelier Manferdini Atelier Manferdini: Guiyang Tower, Guiyang, China (2008)  Prof. I.W. Bailey, Harvard University (“Cleared Leaf”); Edward Weston (“Borero Desert,” 1938) Photomicrograph of a leaf (left), and a boreo desert (right), from "The New Landscape in Art an Science" by Gyorgy Kepes  Lauren Weinhold Peruvian Chincero pattern weaving |

© 2010 ArchNewsNow.com