|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

|

Barry Elbasani, FAIA, 1941-2010: A recent conversation with the gruff optimist and realistic urbanist about his history, inspirations, and aspirations. The architect known for plans and buildings that revitalized American cities passed away last week at 69. By Kenneth Caldwell July 9, 2010 Editor’s note: A memorial for Barry Elbasani will be held Sunday, July 18 at 1:30pm at the Berkeley Repertory Roda Theatre in Berkeley, CA.

Barry Elbasani, who died on June 29th, was a realistic urbanist. He grew up in Brooklyn and on the streets of New York. Through sheer talent (and a little advocacy) he got into Harvard. His one year in Cambridge changed him forever. After leaving the Boston area he moved to Los Angeles for a year, and then to Berkeley where he lived and worked the rest of his life. He told me once, “Berkeley was like Cambridge, but with better weather.” He loved looking at buildings and had a special reverence for Louis Kahn. But he was just as interested in the spaces that buildings frame. Although he came of age in the 1960s, he was not a firebrand radical. He understood that cities need economic activity to thrive. But he also knew that an active public sector can help save a downtown. One of his skills was to bring the developer and the planner together to see what was in their mutual self interest. In the late 1980s and 90s the growth of the Southwest exurbs brought work that wasn’t explicitly urban in nature. Barry’s goal was to make it as urban as possible, and he predicted that the suburb or exurb would densify and that his buildings would become the new town centers. He took the long view.

More personally, Barry Elbasani was a boss who didn’t get in the way – until he did. And then you didn’t know what hit you. He could be aloof, terse, and then, in turn, incredibly kind and voluble. He kept you on your toes. He reached out and gave to all kinds of people, but he never wanted anybody to know. We didn’t let him write anything, but we always let him talk. Creating public space fueled him and his enthusiasm won over clients, city officials, financial types, and nay-sayers of all stripes. He was a gruff optimist.

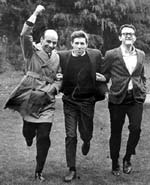

Barry Elbasani founded ELS Architecture and Urban Design in Berkeley with Donn Logan and Michael Severin in 1967, after they won a national competition for the design of the Binghamton Civic Center in Broome County, New York. By the late 1990s, Barry was the only founding principal still involved in ELS. He is the youngest of the original three, and in the 1967 photograph of them taken just after winning the Broome County competition, he looks the most tentative. He had turned over the day-to-day running of the firm to his younger partners, but he was still active in shaping the practice and evolving the original vision. In 2009 we were working on a new book about the firm and sat down to discuss his history and what motivates him. What follows are excerpts from that conversation.

Q: How did you first get interested in architecture?

Barry Elbasani: Back in the 1940s and 50s, if you cared about your kid’s education, you bought them an encyclopedia. Of course, you bought it over time. The first volume to come to our home was “A.” I was thumbing through it, and under “Architecture,” there was a black-and-white photograph of Fallingwater. I must have been about ten. I thought, “I want to do that. “

Q: Were there other early inspirations?

Elbasani: I grew up in Brooklyn, so I had the world’s greatest full-scale mock-up outside the door. In those days, it was safe to take a train anywhere. Society was more benevolent to young children. I had Times Square, Central Park, Prospect Park, MoMA. It was visually exciting and in places very peaceful. As a young kid, I could go out all day and come back at night and nobody worried. That’s where I really experienced buildings, the street, and what the public realm was all about.

Q: Where did you go to school?

Elbasani: Somehow I got into Stuyvesant High, where there was art, music, and mechanical drawing. I knew we didn’t have the money for me to go on to Pratt Institute. So I applied to Cooper Union, which was free, and I was accepted. What I didn’t know was that most of the people who went to Cooper had already gone somewhere else beforehand. Most of the students in my class were at least two or three years older than I was. Back then, you took a fundamentals course that exposed you to people in other disciplines.

Q: How did your non-architecture courses influence you?

Elbasani: In a calligraphy class, I had a Viennese teacher who spoke slowly and quietly. I wasn’t doing well. He had me put down the first letter and then the second, and he said something like. “What is that?” I said, “It’s a letter.” He said, “No, it’s not a letter. It is a building. You are an architecture student, are you not? Now, you are putting another building next to it. It’s shaped like an oval. Before you do it, how close or far should it be?” So I drew it and really understood the idea of spatial relationships. He went on, “From now on you are doing town planning. You are not writing poems. Okay?” It was amazing. The whole idea of space, relationships, intervention, urban design, it came from calligraphy. He knew how to reach me. Cooper was incredible for its discipline and its forgiveness.

Q: Were there lasting relationships?

Elbasani: The most important one that continues to this day was with Dick Bender. He was an architect with an urban planning background as well as an engineer. I crossed paths with him every year at Cooper, and he was the guy who got me into Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Later he was a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and dean of the College of Environmental Design.

Q: Did you want to go to Harvard?

Elbasani: Bender suggested it, and I thought he was crazy. I needed to go to work and make a living. But they got me some kind of loan, and I went. Of course, some people didn’t think I should be there, but it turns out that Josep Lluis Sert intervened—with Bender’s prodding. In addition to Sert, there was Fumihiko Maki and Gerhard Kallmann and Michael McKinnell. It was an incredible year. But again, everybody was older than me, and I was in over my head. There wasn’t so much forgiveness at Harvard.

Q: What was it like?

Elbasani: It was stimulating, but it didn’t really come together for me until the end of the year. At an urban design conference we saw Atelier 5’s design for Halen, the housing project outside Berne, Switzerland. The clarity of the diagram was extraordinary. It was a lean yet dense development that took advantage of its topography and bucolic setting. There wasn’t a wrong note. It had a center and a sense of individual dwelling, but it didn’t take up unnecessary land. Even the units had this great clarity. And I thought, “It’s about the diagram.” This was the beautiful short note, not the long embellished letter. In one lecture, it all came together,

Q: Did you move to Berkeley right away?

Elbasani: No. Urban design was in fashion, and we were in demand. Donn and I both got jobs with Victor Gruen’s office in Los Angeles, and Michael went to Greece with The Architects’ Collaborative. I had never been west of New Jersey. They said I could work closely with Victor, and I had a great year with him. I learned how to present from him. He was incredibly open. He would listen to a 23-year-old punk like me. There was nothing that was irrelevant to him. He would be out of town and would come in a half hour before a big presentation. I would debrief him, and then he could talk about the plan for two hours.

Q: This is when you entered the Fremont Civic Center competition?

Elbasani: Yes, Donn and I did that with Jacques de Brer, who was also at Gruen at that time. Neither Donn nor I had a license. We won second place. Robert Middlestadt, who was a disciple of Paul Rudolph’s, won. Of course, Rudolph was on the jury. But we had a very strong diagram. Then we went after the Birmingham-Jefferson competition, and we came in third on that one. About that time we both left Gruen. Donn got a job teaching at Berkeley and I ended up at the Oakland Redevelopment Agency. Michael wanted to come back to the States, and he also got a job teaching at Berkeley.

Q: And the third time was a charm?

Elbasani: Yup. We worked with a bunch of students up in a garage on Hillsdale Drive. Michael was older than us and was already a licensed architect. He had a lot of experience before he even went to Harvard. I think we won because we didn’t follow the program. They called for putting the arena by the river and the theater inboard. We felt that the theater was more appropriate at the river’s edge, and the arena needed more space. Only the arena got built, which was a big disappointment. We learned a big lesson about communicating budgets and phasing.

Q: How did you name the firm?

Elbasani: Alphabetically. We kept it simple.

Q: What happened next?

Elbasani: We were contacted by a firm in Reston, Virginia, to work on a downtown plan for Yonkers, New York. At the Oakland Redevelopment Agency, I had met a fellow named David Carley. He had run for political office and started a development company that he subsequently sold to Inland Steel. He called and said they had some property in Georgetown and wanted to talk about it. When I got there, I found out they had seven acres in Georgetown from the canal to the waterfront and wanted us to help them master plan it. Inland Steel went on to give us a number of planning commissions, including Monterey Hills in Southern California, and several commissions that led to completed buildings, including Kalamazoo Center; housing in Madison, Wisconsin; and eventually the Mission Inn in Riverside.

Q: Who else was important from the outset?

Elbasani: Steve Dragos. He was running the Broome County competition. Subsequently, he went on to Milwaukee. It’s there that we got together with Laurin Askew and the Rouse Company. Steve worked for several communities helping projects get off the ground. Many years later, he went on to Phoenix, and again we collaborated with Rouse there.

Q: Rouse became a key ELS client. Why was that?

Elbasani: It was like I.M. Pei and New York real-estate developer William Zeckendorf. There was a mutual vision and trust. Rouse enjoyed the collaboration. And Laurin Askew was an architect. When we designed the Grand Avenue in Milwaukee, neither of us had ever done a building like that. But we trusted each other. Each time we were stretching, and our clients were stretching with us. We never quite knew who brought what to the design table. It is often said that design by committee never turns out well. But with the Rouse Company, it worked. There was magic there because everybody cared about the design, not their design. I think we shared the idea that you can’t make a profit without some kind of compelling vision. Jim Rouse always talked about the responsibility to the community, and it was real.

Q: How did Pioneer Place begin?

Elbasani: It was the early 1980s, and we had begun to build a reputation for downtown retail. We got a call from a developer who was having problems negotiating with the city. We presented a series of diagrams that represented at one end the city’s point of view, which would limit the financial viability, and at the other end, the developer’s point of view, which would diminish the experience of the public realm. In the end, the city and the developer couldn’t come to terms, and the deal fell apart. The city then came to us and said, “We are not antidevelopment. How can we make developers feel welcome?”

Q: The city wanted a large project downtown?

Elbasani: Yes. Of course, Portland has an unusual urban fabric, with small 200-foot blocks and beautiful parks. We told them that developers want predictability. It’s hard to be predictable when electoral politics are involved. Administrations change and the rules change. Our advice was, “Don’t change the rules. Don’t be too confining, but be strict with the schedule.” We were hired to do the guidelines for corners, glass, setbacks, and roofs, as well as a schedule. Using that plan, the city sent out an invitation for proposals. We had finished our work and so we resigned as design advisors.

Q: So you could be the architect on one of the teams?

Elbasani: We left the position before any developer approached us, so we would not be in any conflict. Following that, Rouse asked us to be on their team.

Q: After Michael Severin moved to London, were you and Donn collaborating as much?

Elbasani: Donn retired from U.C. Berkeley after teaching there for 20 years. His interest was still urban, but he focused more on the infill projects, like theaters, recreation, and community work. He continued to do a lot of urban design planning as well.

Q: What was the last project you collaborated on?

Elbasani: We worked together on a master plan called Vision 2020 in Hawaii. It was one of the most enjoyable projects we ever did together. It was about the public realm and the future of tropical urban development. Eventually it led to the master plan that we created for Kakaako Makai, which won a national AIA award. In those plans, we weren’t doing buildings per se, we were figuring out design strategies that were also good business.

Q: In the early 1970s and 1980s, a lot of your urban work involved public/private arrangements.

Elbasani: Yes. An urban development action grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development made the Grand Street project in Milwaukee possible. Sometimes the public sector contributes by exercising its power of eminent domain, sometimes by assisting with the provision of parking. But it’s also important to remember that in cities like Milwaukee and Phoenix, you had corporate leaders who cared about their downtowns. There was a sense of community pride that has since been diminished by globalization. Currently, the government is more interested in infrastructure. The money to do great projects in the public realm is going to come from the private sector. Sometimes that public realm space may not make money, but it makes the place that brings in the component that does generate a return, like office space.

Q: Is Arizona Center an example of that?

Elbasani: Yes. The project needed a major office tenant. The retail portion of the project created an edge to the great open space that the SWA Group designed, and over time the retail could follow the market, which turned out to be food and entertainment. But the public space and the restaurants gave the sense of address. Sometimes a piece of the pro forma may not make sense at first—a low-rise building, a collection of shops in a downtown—but the fundamental idea of a respecting a historic landmark, or creating a new open space where there isn’t any, that makes sense. That distinguishes the development.

Q: How did you get into suburban centers as well as urban centers?

Elbasani: Ken Jacobs of Homart saw what we were doing in downtowns and wanted the same vitality in the exurbs.

Q: Isn’t it a different problem?

Elbasani: Yes and no. It’s always about the public realm. But there is a strong context in downtowns and very little context in exurbia. Look at Stonebriar Centre in Frisco, Texas, a place that never had a downtown. If it ever does have a downtown, it will be the mall itself. It was meant to be a next-century kind of space. Something born out of the suburbs can be as exciting for the community as any other civic building, like an opera house, government center, or even an airport. Actually, Stonebriar looks like an airport. You could park airplanes around it instead of cars! But this isn’t a once-every-few-years kind of space; it’s a dramatic space for everyday use. Suburbs are not going to go away, and the best of these centers will evolve and densify. Despite issues with land ownership, the parking lots are actually an enormous land bank. There is enormous potential in these places. We are just placing one piece of the puzzle.

Q: Has the vision of the firm shifted in the last 10 years?

Elbasani: It’s broadened. We’ve gone back to the beginning, to the discussion about the public realm and urban design with many more voices. The result is that the definition of public realm expands. It is not so much about the amount of land or the size of the project, but about the nature of the public experience. You can see it as a wheel, with all the spokes being the different building types we design, but in the middle is the public realm.

Q: How is the economic crisis affecting the markets the firm works in?

Elbasani: What’s happening in the retail/mixed-use market is a blessing for us, in a way. The retail developers who will benefit from the crisis are those who can offer more than a shopping center that looks like 10 others, all of which sell the same exact T-shirt. The ones who will thrive are those who can offer a unique place.

Q: But our economic system seems to be changing?

Elbasani: Ultimately, it may be a good thing, because excess wasn’t good for the local community or the planet. As a group of aligned professionals, we are looking at a mixed-use city in a different kind of way. I don’t mean to suggest that the car is going away, but people don’t want to spend as much time in it, and they want a smaller, more fuel-efficient car that takes up less space and puts out fewer or no toxins. When people live in an authentic mixed-use environment, they don’t need or want to use their cars so much.

Q: How are we getting there?

Elbasani: A lot of sites are being redeveloped. Existing shopping centers are going to become the cores of densifying edge cities. You are beginning to see mass transit coming to them. These places are going through a cycle of redevelopment that will make them mixed use, dense, and more connected to a pedestrian-oriented realm. In some cases, they will become community centers – they don’t have to be retail.

The stage is set for a period of growth because the commercial real estate market has been so devastated. My generation of architects was called to take on urban renewal. The call for the younger generation is not only urban revitalization but also suburban renewal. Out of that will come a wave of really interesting work, hopefully denser, more mixed-use, more sustainable. The new era of development will require firms with a depth of experience in creating and reinforcing a strong sense of place. People don’t want to have to drive everywhere – they want to walk. But to make that work economically, you have to have density. At the same time, you don’t want to damage an area that might have a strong historic core. I don’t think you will see so many heroic projects.

Q: What do you mean?

Elbasani: Our new projects, buildings as well as plans, are more like frameworks. The plan doesn’t take a position on a specific use necessarily. That’s dictated by the marketplace. But there is a strong framework for the public realm that will influence yet not dictate the future tenancy. Heroic, at least in architecture and urban design, means temporary gratification for a powerful object. For all of us, gratification comes from knowing the outlines are there and the place changes and thrives long after we are gone.

Kenneth Caldwell is a writer and communications consultant based in the San Francisco bay area. He can reached at Kenneth@KennethCaldwell.com.

|

(click on pictures to enlarge)  ELS ELS founders Barry Elbasani (far right), Donn Logan, and Michael Severin in 1967, after finding out they had won the Broome County Competition.  Nathaniel Lieberman Broome County Arena, Binghamton, New York, 1973: The firm's first completed building, the Broome County Civic Center, was on the cover of Architectural Forum and received several design awards.  Eric Oxendorf The Grand Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1982: Elbasani's collaboration with The Rouse Company on The Grand Avenue helped revitalize downtown Milwaukee.  Greg Hursley The Shops at Arizona Center, Phoenix, Arizona, 1990: Another collaboration of Elbasani and The Rouse Company was the retail center and park at Arizona Center that created a sense of place in downtown Phoenix, resulting in leases for the office buildings in the complex.  Timothy Hursley Pioneer Place, Portland, Oregon, 1990: Elbasani was involved in the initial design guidelines and plans that helped shape downtown Portland. His work on the multi-block Pioneer Place over two decades has been recognized for responding to the pattern of the city and also serving as a catalyst for the downtown district's revitalization.  Timothy Hursley Church Street Plaza, Evanston, Illinois, 2000: The new retail precinct in downtown Evanston leverages the strong pedestrian flavor to keep shoppers downtown and create demand for future office space.  Timothy Hursley Stonebriar Centre, Frisco, Texas, 2000: Elbasani believed that, as suburbs evolved and densified, exurban retail centers would eventually be remade as town centers.  ELS Kakaako Makai Areas Master Plan, Honolulu, Hawaii, 1994: Elbasani's fine-grain urban design plan for a neighborhood in Honolulu received a national AIA Urban Design Award. |

© 2010 ArchNewsNow.com