|

|

|

|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

|

|

From Confinement to Liberty: The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center by Blackburn Architects with BOORA Architects

Cincinnati, Ohio: A riverfront museum embodies the geography of escape. By John Meadows, AIA November 17, 2006 "Her first glance was at the river, which lay, like Jordan, between her and the Canaan of Liberty on the other side." – Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, 1852

Founded in 1994, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio, has a twofold purpose: to teach visitors about the clandestine system of paths and guides that helped runaway slaves escape from their owners in the 1800s, and to give testimony to the ongoing struggle to achieve freedom from all kinds of slavery and oppression across the globe. Cincinnati was one of the Underground Railroad's main stations because of its location just across the Confederate line. The organization chose a prominent site for the new 150,000-square-foot facility on a bluff above the Ohio River across from Kentucky.

When the Freedom Center was in design, the museum's administrators received a call from farmer Raymond Evers of Mason County, Kentucky. The old tobacco barn on his property housed a pre-Civil War slave pen, which he was interested in donating to the new museum. This roughhewn 20-foot-by-30-foot log structure was a historic find – but it would require the Freedom Center and its design team, Blackburn Architects in association with BOORA Architects, already halfway through design development, to rethink the new building in a significant way.

In the early 1800s, there were thousands of slave pens across the South. They served as cramped holding cells for slaves being force-marched on long journeys westward from Virginia to be sold at auction. All but a scant few of these buildings have been torn down, lost to posterity. This one had survived only because it had been concealed in a barn, protected from the weather.

When the design team visited Evers’s property with museum officials, they found a two-story holding pen, chains still attached to the walls, shafts of light falling through age-blackened clapboards of sycamore and walnut. The power of the artifact was immediately clear. “The decision was made that this was something we had to have, even though it meant we had to adjust our design,” says Paul Bernish, chief communications officer for the Freedom Center. “This is the largest artifact in the museum by far – it's one and a half stories tall.”

The challenge was to incorporate the discovery into the design already in progress. The Freedom Center’s 8,000-square-foot welcome hall was a logical site, but there was no space large enough to fit a 35-foot-tall structure. And the hall had been envisioned as a bright, festive place, celebrating the courage of those who fought so bravely for freedom. The chilling presence of the slave pen seemed to call for a design that reflected the hardships as well as the courage to overcome them.

The design team had given the building a form that embodied the geography of escape. Since the runaway slaves followed circuitous routes, through the rolling hills of the landscape, to cross the meandering Ohio River, these curves are echoed in the undulating stone walls that flank each of the museum’s three pavilions and the curving roofs. And while Ohio had banned slavery, federal law still allowed the capture and return of escapees. Those traveling the Underground Railroad couldn't rest once they crossed the river, but had to continue on farther north to elude bounty hunters. To capture this sense of continual movement, curving north-south paths extend between the three pavilions, allowing visitors to walk through the building between the riverfront and the downtown. On the exterior, the materials evoke the sometimes harsh struggle to achieve liberty, with rough travertine stone blocks chosen for the curving walls on the sides of the pavilions, weathered copper cladding, and granite from Zimbabwe.

The facility’s pavilions contain exhibit space, story theaters, a 325-seat multiuse theater, educational facilities, a research institute, a café, and a gift shop. By breaking the building into three pavilions, connected by glazed skybridges, the design reduces the apparent mass of the building and brings it down to a more human scale.

To incorporate the slave pen and make it the defining feature of the visitor experience didn’t require altering the basic design concept. But it did require significant changes in the use of space. To make room for the slave pen in the central pavilion's welcome hall, the designers moved the spiral staircase and elevators and eliminated the second floor. Circulation routes throughout were altered so that the slave pen not only greets visitors when they first enter the building, but also comes into view multiple times as they wander through the center, deepening its resonance as they learn more about the Underground Railroad and the history of slavery. In addition, the amount of glazing in the welcome hall was increased to make the structure visible from downtown Cincinnati on one side and along the riverfront on the other. On the roof terraces facing the river, an “eternal flame” serves as a reminder of the candles placed in the windows of “safe houses” where abolitionists sheltered escaping slaves.

The design team toned down the celebratory atmosphere of the welcome hall, taking a more stripped-down approach to let the raw power of the slave pen speak for itself. A ramp and terrace theater that originally occupied the welcome hall was removed. Splitface stone walls on the interior were replaced with smooth stone to allow the texture of the log slave pen to stand out. The slave pen was meticulously disassembled, transported across the river, restored, and reassembled inside the welcome hall.

The slave pen’s presence in the welcome hall serves as a powerful way to make the history of slavery real to present and future generations. “Some visitors, particularly African Americans, have said they feel like they are entering a holy place when they walk into the slave pen,” says Bernish. “Some have broken down when they see it. It has become the icon of the Freedom Center, even though we haven't promoted it that way.”

The Freedom Center opened in August 2004, and in its first year alone drew 280,000 – 20,000 more than museum officials projected. One concern was that the slave pen might prove so somber a memorial that rentals of the 6,800-square-foot grand hall for events – increasingly an important source of revenue for museums – would be low. However, the hall has proven to be a highly popular site, hosting everything from business events and bar mitzvahs to weddings and family reunions. And a once-oppressive space of confinement is now part of a story of freedom.

The project is part of a $1 billion riverfront redevelopment project that also included new baseball and football stadiums on either side. A historic bridge designed by John Roebling lies just to the south of the site. Taking center stage in the city’s skyline, the building serves as a new front door for Cincinnati.

John Meadows, AIA, is a principal of BOORA Architects and was Principal-in-Charge of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. He was the first architectural principal in Oregon to become certified as a LEED Accredited Professional.

Project credit list

Design Consultant: BOORA Architects Lead Architect: Blackburn Architects General Contractors: Dugan & Meyers Construction; Megen Construction Company Structural Engineer: Charlier, Clark & Linard Mechanical/Electrical Engineer: Burgess & Niple Landscape Architects: Hood Design; Martha Schwartz, Inc. Civil Engineer: JMA Consultants Acoustical Consultant: The Talaske Group Lighting Consultant: Auerbach Glasow Architectural Lighting Design Theater Consultant: Auerbach Pollock Friedlander Exhibit Consultants: American History Workshop; Jack Rouse Associates Food Consultant: Cini-Little International

Founded in 1958, Portland, Oregon-based BOORA Architects is an architectural practice with a staff of 85 providing architecture, planning, and interior design services. The award-winning firm is noted for innovative responses to resource scarcity, evolving social norms, and new technologies in areas that include: the arts; higher, primary, and secondary education; housing; recreation; and government.

Blackburn Architects is an Indianapolis, Indiana-based multi-disciplinary firm offering architectural, planning, and interior design services for corporate, education, multi-family housing, religious, and government clients. |

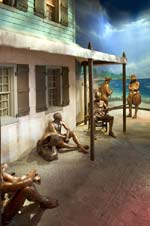

(click on pictures to enlarge)  (J. Miles Wolf) National Underground Railroad Freedom Center: evening view between the building pavilions (Assassi Productions) Evening view of south elevation (Assassi Productions) The south elevation with museum entry (Assassi Productions) View of the Welcome Hall, Central Pavilion, second floor (Assassi Productions) The Slave Pen in the Welcome Hall, Central Pavilion, second floor (Assassi Productions) The entrance to the “From Slavery to Freedom” exhibit, West Pavilion, third floor (Assassi Productions) View of the “From Slavery to Freedom” exhibit (Assassi Productions) An experience in the “From Slavery to Freedom” exhibit (Assassi Productions) “From Slavery to Freedom” exhibit detail (Assassi Productions) “The Struggle Continues” exhibit, East Pavilion, third floor (Assassi Productions) “Everyday Freedom Heroes” exhibit, East Pavilion, third floor (Assassi Productions) “Reflect. Respond. Resolve.” the concluding experience exhibit, East Pavilion, third floor (Assassi Productions) The “Suite for Freedom” auditorium with January 1, 1863 night sky, West Pavilion, second floor (Assassi Productions) Overall perspective from the south (Blackburn Architects with BOORA Architects) Cincinnati waterfront site plan (Blackburn Architects with BOORA Architects) Site plan and first floor plan (Blackburn Architects with BOORA Architects) Second floor plan (Blackburn Architects with BOORA Architects) Third floor plan |

© 2006 ArchNewsNow.com