|

|

|

|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

|

|

Sex and the City Part 2: Field Notes from the 10th Venice Architecture Biennale

The message seems to be that if we merge greater intelligence about the common good with our traditional urge to procreate as individuals, we might have half a chance to thrive as a species several generations hence. By Margaret Helfand, FAIA September 14, 2006 Part 1: "Cities, Architecture and Society": Libidos on fire in Venice

Curator Ricky Burdett is not the only one thinking about sex at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale. Spain has taken a brazenly gendered stance with its offering “Spain (f.) We, the Cities,” and starts by noting that both the country’s very name (España) and the Spanish word for cities (ciudades) are gendered female in the Spanish language. The beautifully conceived and presented exhibition energetically commands the space with a tight grid of 55 video screens presenting 100 talking heads (f., of course, and talking torsos if we must be precise). The first head to be encountered is that of Spain’s Minister of Housing, Maria Antonia Trujillo, who states in no uncertain terms, “There is no sustainable urban development without a female perspective.” That perspective is convincingly articulated by the 99 other heads, which are drawn from a cross section of Spanish citizens – architects, landscape architects, urbanists, elected officials, artists, sociologists, immigrants, a bar owner, firefighter, taxi driver, ecologist, and bicycle rider. But all is not just talk. The 32 elegant and humane urban projects illustrated on the backs of the interview panels make a compelling case for the proposition that the world might be a better place if women were in charge, in government as well as the design professions.

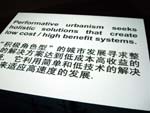

The Danish, in a characteristic gesture of collaboration, have partnered with the Chinese to present “Co-Evolution,” an innovative and inspiring collage of strategies for sustainable urban development in China – arguably the biggest Petri dish on the planet for testing concepts for city building in the 21st century. To make their point, the entire pavilion is shrouded in construction netting and scaffolding and plastered with billboard-size quotations from the four teams of young Danish firms partnered with students and professors from top Chinese universities. Inside is an ad-hoc array of panels, models, and videos urgently fighting for your attention. One riveting installation is a video projected onto the top of a plywood box. In a sequence of text in English and Chinese and elegant graphics, CEBRA + Tsinghua University depicts a strategy called “Performative Urbanism” for transforming a highly polluted industrial area in eastern Beijing’s green belt into a new satellite city of seven small urban districts. By increasing density and increasing height towards the center, the ground plane grid between the districts is reserved for transportation, recreation, and community functions, while commercial and residential towers create an iconographic topological skyline for the city.

The U.S. pavilion also showcases its national character. In a bootstrap operation, Architectural Record magazine curated its third Biennale with the patronage of Autodesk (the manufacturer of Autocad software), last minute support of the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the U.S. Department of State, and backing from a number of large and small architectural firms. It is a full-frontal presentation of pro-bono American moxie – perhaps the most valuable U.S. export in current times. On display are a collection of advocacy projects by architectural firms and students generated in a recent competition for multi- and single-family housing, sponsored by Architectural Record, to respond to the largest natural disaster to have affected the United States in its entire history – Hurricane Katrina, which largely destroyed the city of New Orleans in 2005. In an intelligent, multi-layered proposal, San Francisco-based Anderson Anderson Architecture managed to roll sustainability into libidinous form while recycling waste and gray and storm water on site (underground); employing vegetated louvers as adjustable façade shading to filter roof rain water; providing natural ventilation on four sides by alternating placement of the prefab modules on the structural space frame grid; and elevating habitable space above the flood plain by dedicating the ground level to bicycle and car parking and limited commercial space.

Leaving aside the question of whether cities such as New Orleans should be rebuilt or not, some countries chose to address the question of urbanism on a radically different scale. Arguing for the value of intimacy on a personal level in the midst of global urbanization, Finland, Japan, and the Netherlands offer exceptionally thoughtful responses. Immediately adjacent to the always overwhelming Italian Pavilion, but tucked back slightly under the trees in the Giardino, Alvar Aalto’s Finnish Pavilion (actually a tiny cottage) simply and elegantly presents “City Home,” adaptive reuse and new residential architecture in the Helsinki region – aah – a breath of fresh Scandinavian air.

Also looking in a different direction, Japan presents a collection of work by the iconoclastic artist/architect Terunobu Fujimori. His urban houses, small museums, and tea houses employ traditional materials and forms in creating sustainable and searingly memorable neo-primitive structures, such as the Leek House, whose sweeping shed roof is planted with a grid of flowering leeks. The Dutch, always with an original perspective, offer an exquisite historical survey of architectural drawings from the late 19th through 21st centuries depicting commissioned urban projects. Aiding and abetting this minority stance of equanimity among some nations in the face of impending planetary dysfunction, the Nordic Pavilion itself embodies an instructive, generous, and refreshing concept of one successful relationship possible between man and nature.

So where does this leave us design professionals, struggling to move architectural history forward in a positive direction? If evolution is survival of the fittest (a theory still debated, unfortunately, in some corners of the world), the message from the 10th Architecture Biennale seems to be that if we merge greater intelligence about the common good with our traditional urge to procreate as individuals, we might have half a chance to be alive – and maybe thrive as a species several generations hence. Burdett appears to have garnered a ringing endorsement across this landmark international exhibition for a new definition of architectural “fitness” as a new, more intelligent balance between mind and body on that primordial continuum. Smart sex anyone?

Margaret Helfand, FAIA, is founder and principal of New York City-based Helfand Architecture.

Also by this author: Observations from the

Field: Metamorphosis and Transcending Hype

|

(click on pictures to enlarge)  (Jon Turner) Spanish Pavilion: 100 talking torsos (Cemal Emden) Spanish Pavilion installation (Carme Pinós Desplat) Spanish Pavilion: Torre Cube, Guadalajara, by Estudio Carme Pinós (Jon Turner) Danish Pavilion: Performative Urbanism (Jon Turner) Danish Pavilion: Beijing satellite city (Jon Turner) U.S. Pavilion: Population vs. Time and indicating Historic Hurricane strengths in New Orleans (Jon Turner) U.S. Pavilion: CamelBackShotGunSpongeGarden housing for New Orleans (Jon Turner) Finnish Pavilion: Urban housing in Helsinki (Jon Turner) Japanese Pavilion: Terunobu Fujimori’s Leek House (Jon Turner) Netherlands Pavilion: Mixed use project incorporating trolley portal in Amsterdam (Jon Turner) Nordic Pavilion: Living forest |

© 2006 ArchNewsNow.com