|

|

|

|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

|

|

INSIGHT: Condos Breathe New Life into Old Offices

Historic office buildings are increasingly being reinvented as condominiums in CBDs (central business districts) across the country. by Mark Harbick, AIA November 29, 2005 Historic office buildings are a hot item these days – but not for office tenants. Urban housing shortages, low mortgage rates, and soft office leasing markets are resulting in a wave of condo conversions, as historic downtown office buildings find new life as luxury condos.

San Francisco provides a good example. Hit hard by the dot-com bust, the city saw its office vacancy rate shoot up from about 2% in 2000 to a peak of more than 20% in 2002. While the office market has been steadily recovering – for the second quarter of 2005 vacancies were at 18.5%, according to Grubb & Ellis – long-term job losses and a shortage of housing have made conversions of Class B and C office buildings too tempting to resist. These structures can’t compete with the larger floor plates and flexibility of Class A office buildings, and with office absorption several years out (5 to 10 years according to some estimates), simply renovating these buildings for office use doesn’t make sense financially. Meanwhile, housing prices have risen high enough in the past few years that the cost of renovating old offices into condos is worth it. Over a dozen conversion projects are now in the works in the city’s central business district (CBD). Other urban cores across the country show a similar trend.

Converting historic buildings can require not only adapting offices into places suitable for residential living, but also addressing the interventions of previous owners who modified the buildings. One of the first downtown conversions in San Francisco was the former Home Telephone Company at 333 Grant Avenue between Sutter and Bush Streets, designed by Coxhead and Coxhead and built in 1908. The building featured a stone lobby, intact plaster ceilings, and double-height top floor (which once housed large telephone switching gear racks). The design strategy by Huntsman Architectural Group was to remain faithful to the historic fabric of the building while addressing its modern-day use. The exterior of the building was carefully restored to its original grandeur. Wherever possible, original brick, sandstone, steel, and concrete were left exposed on the interior of the building to recall the building’s history. Unit interiors and public spaces were conceived as a contemporary intervention.

Another example is 74 New Montgomery, a mid-rise office building built in 1914 by the noted local firm of Reid Brothers Architects. Originally constructed as the headquarters of the San Francisco Call newspaper, the unusual building has two nearly identical façades. When Huntsman completes renovations in 2006, it will house more than 100 residences, including four new penthouse units and a roof deck. The project includes a seismic retrofit and complete renovation of the building's interior. Like 333 Grant, the residences will feature contemporary interiors to contrast with the historic exterior.

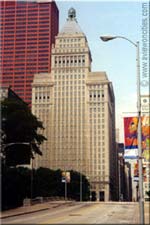

The candidates for conversion include some famous architectural gems. In Chicago, Holabird & Root’s 1929 Palmolive Building at 919 North Michigan Avenue, an icon of the Art Deco period, is undergoing conversion into 103 luxury condominiums, designed by Chicago-based Booth Hansen. And the 1920s-era Straus Building (later known as the Britannica Center) at 310 South Michigan Avenue, designed by Graham, Anderson, Probst & White in 1924, will be converted into the Metropolitan Tower with 245 condos by 2007, designed by Pappageorge/Haymes, with the famous stepped pyramid and blue beacon at its apex retained.

The conversion of these kinds of buildings can have a noticeable influence on the office market. In Forth Worth, Texas, the office market is currently so strong that Class B office space in the central business district is more than 95% leased. Part of the reason is that a significant percentage of Class B space has gone off the market in recent years – much of it earmarked for residential conversion. The largest of these is the 1 million-square-foot Charles D. Tandy Center at Second and Throckmorton Streets, formerly RadioShack’s headquarters, which the current owners removed from the market in 2004. They plan to transform at least one of the Tandy Center’s 1970s-era towers into condominiums.

A number of the current office-to-condo conversions in downtown Fort Worth involve historic buildings. The 101,000-square-foot Neil P. Anderson Building at 411 West Seventh Street, an 11-story high-rise designed by Sanguinet & Staats in 1921, is slated for conversion by Dallas-Ft. Worth-based project architect Corgan Associates into 60 condominiums. Currently Class C office space, it was once the headquarters of the Neil P. Anderson Cotton Company; the entire eleventh floor, originally built as a cotton exchange showroom with seven large skylights, will be turned into a penthouse unit. And the 12-story art deco Texas & Pacific Railroad Terminal building at West Lancaster Avenue and Throckmorton (Wyatt C. Hedrick, with Herman Koeppe, 1931), will eventually house 130 apartments on its upper floors. The latter project received $2.8 million from the tax increment financing district, and is part of the city’s new $14 million revitalization of Lancaster Avenue.

The success of office conversions isn’t going unnoticed by the hotel industry. In San Francisco, both the Fairmont Hotel and the Palace Hotel are considering converting some of their rooms into condos. Located on Nob Hill, the Fairmont, built in 1906, is one of the city’s landmarks – although the rooms being considered for conversion are located in an undistinguished 29-story addition constructed in 1961. The current incarnation of the landmark Palace Hotel, right next to the Financial District, opened in 1909. Although neither hotel has even filed for an application yet, the president of the city’s board of supervisors proposed a ban on converting hotel uses to condominiums, arguing that the conversions would put many hotel workers out of their jobs. While the Fairmont’s plans would include converting only 60 rooms, the issue has been controversial, likely because of ongoing concerns about hotel worker jobs in the city – contract negotiations between the hotel union and 14 of the city’s hotels have been at a standstill since August 2004. In August 2005, the board of supervisors voted on compromise legislation that imposes an 18-month moratorium on hotel-room-to-condo conversions to give time for an economic impact study.

Another model is for office buildings to be converted into time-share units. The original Chronicle Building at 690 Market, designed by Burnham and Root and constructed in 1889 (rebuilt by Willis Polk after the 1906 earthquake), is one of San Francisco’s best kept architectural secrets. In the 1960s, an enameled porcelain skin was installed over the richly ornamented brick and sandstone façade in an attempt to “modernize” the building. The current renovation project, by architect Charles Bloszies, AIA, and preservation specialist Page & Turnbull, will remove this modern skin and restore the landmark façade, as well as add eight new floors to the top of the structure. When completed, the structure will house both for-sale condominiums and time-share suites.

At some point, of course, the market for condos is likely to become saturated. In San Francisco, construction is starting on Millennium Tower at 301 Mission Street, a block away from the edge of the Financial District, adding 420 upscale condos to the housing supply. Just three blocks from the Financial District, a 656-unit luxury condominium tower is going up at 300 Spear Street (Heller Manus Architects), to be completed in 2007. Add to this 100 units at the recently completed St. Regis Tower (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill), at Third and Mission Streets, not to mention several hundred new condo units in the nearby neighborhood of Mission Bay. While the older, converted office buildings offer the cachet of true downtown living and the attraction of historic features, there’s one more limiting factor – the supply of easily convertible historic office buildings. In addition, low mortgage rates won’t last forever. A significant rate increase may put a damper on demand for condominium developments of all types. How this affects the conversion market is anybody’s guess.

Of course, as Trevor Boddy points out in “Downtown Vancouver’s Last Resort: How Did ‘Living First’ Become ‘Condos Only?’” the danger of a city acquiring too many downtown condos is that it can result in a shortfall of office space – and lower tax revenue. One of the issues San Francisco will explore in relation to the hotel-to-condo question will be the difference between the potential condo property taxes and the income from the hotel room tax on those same rooms. Although San Francisco has a larger corporate base in its downtown than Vancouver does, city planners may find it worth investigating how the office-to-condo trend will similarly affect property taxes.

Ultimately, the conversion of these buildings is the result of a strong residential market and a soft office market. Cities and developers have awakened to the value of historic landmarks and are incorporating them into the economic life of their downtowns. Given the lax office market and the still-growing demand for downtown living, the projects that feature architectural character are likely to remain hot for some time to come. Even if the downtown condo market does become saturated, the opportunity to live in a historic landmark will most likely remain an advantage in the eyes of buyers.

Mark Harbick, AIA, is a partner at San Francisco-based Huntsman Architectural Group. |

(click on pictures to enlarge)  (David Wakely) 333 Grant Avenue, San Francisco (Coxhead and Coxhead, 1908): a landmark phone company building converted to residential condominiums in the city’s central business district – Huntsman Architectural Group (Huntsman Architectural Group) 74 New Montgomery, San Francisco (Reid Brothers Architects, 1914): originally headquarters for San Francisco Call newspaper; conversion will include four new penthouse units and a roof deck - Huntsman Architectural Group (Draper and Kramer/www.palmolivebuilding.com) Palmolive Building, Chicago (Holabird & Root, 1929): undergoing conversion into 103 luxury condominiums – Booth Hansen (www.aviewoncities.com) Straus Building/Britannica Center, Chicago (Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, 1924): conversion to 245-unit Metropolitan Tower – Pappageorge/Haymes (www.fortwortharchitecture.com) Neil P. Anderson Building, Fort Worth (Sanguinet & Staats, 1921): slated for conversion into 60 condominiums – Corgan Associates (Tim Griffith) St. Regis Hotel & Residences, San Francisco – Skidmore, Owings & Merrill |

© 2005 ArchNewsNow.com