|

|

|

|

|

|

Home Site Search Contact Us Subscribe

|

|

|

|

INSIGHT: Old Governor's Mansion: Turning a House into a Public Building

Milledgeville, Georgia: A preservation architect explains how HVAC systems were integrated and life safety codes addressed without destroying the historic fabric of a National Historic Landmark. by Susan Turner, AIA August 9, 2005 The citizens of Georgia have long regarded their Old Governor’s Mansion as a state treasure. Designed by architect Charles B. Cluskey and completed in 1839, the imposing structure is often cited as one of the finest examples of Greek Revival architecture in the country and has been designated as a National Historic Landmark. It occupies most of a city block in Milledgeville, the central Georgia city that served as the state’s capital from the early 1800s – until the hurried exit of Governor Brown from the building during the Civil War.

Since then, the house has seen many uses. Throughout the latter 19th and early 20th centuries, it served as a university dormitory, first for Georgia Normal and Industrial College, the predecessor of its current owner, Georgia College & State University. In the 1960s, the building was first restored to serve as a house museum. In more recent years, the university has used it as the university president’s office and as a hostelry for overnight VIP guests.

Adaptation of historic structures to meet modern needs is one of preservation architects’ greatest challenges, and a good example is Georgia’s Old Governor’s Mansion. Throughout the course of its restoration, Lord Aeck & Sargent and the design team worked diligently to minimize the potential intrusions that new functions can bring.

A primary goal of the restoration was to return the building to service as a house museum, interpreting the lives of Georgia’s governors during the early 1850s. The house will be occasionally leased for special events, such as weddings, and the university will continue to hold important gatherings in its grand public spaces – continuing its original purpose as a gathering space for community and state events.

The building’s main entrance is through a pedimented portico of the Ionic order. The exterior is clad in stucco, scored to simulate large stone blocks; its pale pink tint is from the native red clay that was an ingredient in the original lime stucco. Granite coursing and column bases and capitals provide rich detail. The building has three floors: the lower contained mostly service functions; the middle or main floor served public functions; and the upper floor was the family’s living quarters. A two-story rotunda, starting at the main floor and piercing the second floor, is topped with an ornate plaster dome and serves as the grand focal point of the house.

While the Mansion’s role today does share many similarities with its historic usage, it is impossible to escape the reality that it was designed primarily for residential use. Transforming it from a house to a public building created numerous challenges.

To achieve a highly accurate restoration, all design decisions were based on careful research and evaluations to minimize the potential impact on historic materials and spaces. Integrating new systems and functions into the historic structure required careful adaptation to ensure that today’s technologies and life safety codes did not damage the historic fabric and had minimal visual impact on the restored spaces.

Integration of HVAC Systems

Restored interior spaces of the Mansion required climate control to protect collections and maintain comfort levels for periodic public events with relatively large crowds. Several different system types, including fan coil units, high velocity forced air systems, and conventional forced air systems, were evaluated. The existing system was a fan coil unit system, and chronic leakage of the condensate drain lines had caused substantial water damage in the building. This experience made the client wary of this type of system. High velocity forced air systems were determined to be unable to accommodate the cooling loads anticipated during large gatherings. Ultimately a decision was made to use a conventional forced air system.

This system type met the mechanical and maintenance goals, but a primary design challenge was installing the system in a building that was not designed with space to locate equipment or run ductwork. Additionally, devices had to be integrated into the period spaces without drawing attention. Fortunately, a large unoccupied attic was available for equipment location.

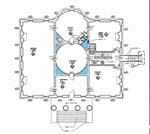

Four small triangular spaces around the central rotunda were used for vertical duct chases. Since it was critical to maintain the historic ceiling heights (plaster applied directly to the underside of the ceiling joists), all horizontal duct distribution had to be routed between the ceiling joists. This often required splitting ducts into multiple small ducts sized to fit between the joists.

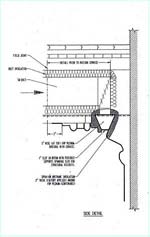

The installation of equipment and ductwork required meticulous coordination, but a greater challenge proved to be introducing the air into the period spaces. The grand public rooms on the main floor had plaster ceilings. Originally these ceilings had ornate plaster cornices that had been replaced with wood cornices in the 1960s. The restoration envisioned replicas of the original plaster cornices with a narrow slot diffuser integrated into one of the wider spaces in the molding. While the diffusers can be seen if standing directly beneath them, when viewed obliquely, they disappear into the shadowlines of the cornice. In the few spaces that still had an original cornice, the slot diffusers were installed in the plaster ceiling immediately in front of the cornice. While more visible, the design team recognized the remaining original cornices as historic fabric that should not be altered.

The task on the upper and lower floors was much easier with a crawl space and attic to run ductwork. Floor grilles and slot diffusers were again strategically located to reduce visual impact. Where possible, grilles were incorporated into architectural elements that had to be reproduced, leaving historic materials untouched. An example of this can be found in the storage room that served as the larder for the kitchen. Here, floor-to-ceiling cabinets required reconstruction. The upper cabinets were used to run ductwork, and supply grilles were concealed using a perforated metal cabinet door that resembles a pie safe.

By using the large central rotunda as a return air plenum, return air grilles in the period spaces were not necessary. Doors were slightly undercut to facilitate air movement. Return grilles were disguised in millwork on the upper floor and ducted into the attic. One example of this is in the historic linen storage room. It, too, was originally lined with floor-to-ceiling cabinets for household supplies. Replica cabinets were designed without glass in the upper cabinet doors, allowing return air to enter the cabinets and then be exhausted through a grille in the top.

Fresh air intake for the mechanical equipment in the attic posed another challenge. The design team wished to avoid the installation of air intakes on the roof. The solution was a narrow slot in the ceiling of the portico that allows air to be ducted into the attic. The slot is concealed behind a large dropped beam, making it making it almost invisible.

The restored spaces of the Old Governor’s Mansion were designed to contain all new systems including: heating, ventilating, and air conditioning; electrical; fire protection (sprinkler); fire alarm; emergency lighting; and security. Each of these systems was integrated into the historic architecture in a manner similar to that described for the HVAC systems, taking great care to minimize all physical and visual impact on the historic structure.

Addressing the Life Safety Issues

Another significant challenge lay in adapting the building to meet present day life safety and accessibility codes. A code analysis identified all code-related deficiencies. Close collaboration with the State Fire Marshal aided in the development of alternative means of code compliance that minimized the impact of modern intrusions while accomplishing the goals of public safety and accessibility.

The project was greatly aided by Georgia’s Landmark Museum Building code, designed with the special needs of historic structures in mind. The solution to many of the building’s code issues was in dividing the building into zones based on intended use to limit the scope of intervention required. Public events are limited to certain designated areas, and tour groups to other areas are kept small and always guided by staff familiar with the house and exit routes. This means modern devices, such as exit signs, fire alarm pulls, and strobe lights, are installed in public-use zones only.

Devising zones was also useful in solving structural issues. The building’s structural systems were designed to carry residential loads and required significant reinforcing to meet the structural demands of a 21st century public building. Great efforts were made to retain the original wood structural members, reinforcing rather than replacing them. Major reinforcement was carried out in the public-use spaces, and specifically designated tour routes helped in limiting areas of structural intervention.

Accommodating Modern Demands

Several new “outbuildings,” designed in the spirit of early outbuildings, house support functions such as public restrooms, catering kitchen, gift shop, and a display and video presentation area. To have located these services within the house would have severely impacted the structure. The accessible entrance to the Mansion is through one of the outbuildings connected to the rear of the house.

The result of these efforts is a faithful restoration of one of Georgia’s most significant public buildings that conveys its rich history – and will allow it to continue to serve as an important gathering space for the public for many years to come.

Susan Turner, AIA, is a principal at Lord, Aeck & Sargent and leader of its Historic Preservation Studio in Atlanta.

Project Credits: Owner: Board of Regents, Georgia College & State University Owner’s Cost Consultant: The Christman Company Construction Manager: Garbutt / Christman Joint Venture Architect: Lord Aeck & Sargent Associated Architect: Architects 4, Inc. MEP&FP Engineer: Andrews, Hammock & Powell Preservation MEP&FP Engineer: SWS EngineeringStructural Engineer: Robert Darvis Associates Civil Engineer: Dames & Moore / URS Archeology: Southern Research Finishes Analysis: Sara B. Chase Historian: Dr. William Seale Stucco Consultant: Andrew LadygoPhotography: Jonathan Hillyer

Founded in 1942, Lord, Aeck & Sargent serves clients in scientific, academic, historic preservation, arts and cultural, and housing and mixed-use development markets. The firm has offices in Ann Arbor, Michigan; Atlanta; and Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Editor’s note: To date, the Old Governors Mansion has won a number of awards including: -- Two awards from the Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation: Marguerite Williams Award for the project’s significant impact on preservation during 2004, and a 2005 Excellence in Restoration Award. -- Associated General Contractors (Georgia Branch) 2005 Build Georgia Award for Construction Management Renovation $100 million+ -- Grand Award in Building Design & Construction’s 22nd annual Reconstruction & Renovation Awards Competition

|

(click on pictures to enlarge)  (© Jonathan Hillyer) Old Governor’s Mansion restored rotunda (© Jonathan Hillyer) Restored Mansion (Georgia College & State University) Antebellum rendition of the Old Governor’s Mansion (Georgia College & State University) Historic photo showing dormitory addition (© Jonathan Hillyer) Restored Saloon, main public space (© Jonathan Hillyer) Restored bedroom (© Jonathan Hillyer) Restored kitchen (Lord, Aeck & Sargent) The attic is used for equipment location (Lord, Aeck & Sargent) Plan showing vertical duct chases in blue (Lord, Aeck & Sargent) Ductwork installed in vertical chase (Lord, Aeck & Sargent) Ductwork installed between joists (Lord, Aeck & Sargent) Detail of diffuser (Lord, Aeck & Sargent) Diffuser in plaster cornice (© Jonathan Hillyer) Cabinets used for return air in restored linen room (Lord, Aeck & Sargent) Detail of cabinet in linen room (Lord, Aeck & Sargent) Return air grille in portico ceiling (Lord, Aeck & Sargent) Plan highlighting public-use areas (Lord, Aeck & Sargent) Reinforcement of historic floor joists (© Jonathan Hillyer) View of new outbuildings (© Jonathan Hillyer) New video and museum space |

© 2005 ArchNewsNow.com